Since 2014, University City High School has reduced suspensions by more than 40% and dramatically changed its school culture. Rowhea Elmesky, associate professor of education, and Olivia Marcucci, PhD ’19, helped make it happen.

Just two miles from Washington University’s Danforth Campus lies University City High School, a stately Art Deco-styled brick building that first welcomed students in 1930. Today, the school serves some 800 students, many of whom are low-income and approximately 90% of whom are students of color. Rowhea Elmesky, an associate professor of education in Arts & Sciences, first entered the high school’s doors back in 2014. At the time, administrators were working through a seemingly intractable problem.

“The district’s concerns were largely achievement-based, as they wanted to make sure that their high school students would be able to pursue different academic pathways or just be successful as individuals,” Elmesky said. “They started to notice, however, that a barrier standing in the way of this goal was the overall school culture.”

In the three years leading up to 2014, UCHS recorded approximately 4,000 disciplinary infractions, including a significant number of suspensions. In one class Elmesky observed, the teacher was unable to talk over or even make eye contact with students. Simply put, the school’s culture was in need of a fundamental shift.

A budding partnership

Recognizing the scope of the problem, former assistant superintendent Chauna Williams reached out to Washington University’s Institute for School Partnership (ISP) with the seed of an idea: Perhaps through a collaboration with WashU, researchers and school staff could help identify solutions to revitalize the culture at UCHS. Victoria May, ISP’s executive director and assistant dean in Arts & Sciences, in turn reached out to Elmesky, whom she knew as both an education researcher and personal friend.

“It's interesting how it began, because I'm a science educator by training,” Elmesky recalled. Alongside her teaching experience, her research background was a strong fit for a partnership with UCHS. “I consider my expertise to be inner-city school environments and the sociocultural dimensions of classrooms and schools,” she explained. In her research, she uses qualitative methods to do long-term ethnographic studies through an anti-racism and equitycentered lens. Her work focuses on not just understanding problems, but enacting change.

After an initial hand-off meeting with May, Elmesky and doctoral student Olivia Marcucci, now an assistant professor of education at Johns Hopkins University, got to work. They conducted focus groups with as many stakeholders as they could find: students, student groups, administrators, teachers, and staff. With each group, they sought to answer a simple question: Why do you think this is happening?

A trust problem

The focus groups revealed that a basic lack of trust affected nearly every facet of school life. Students felt distrusted and disrespected by teachers, and vice versa. In some instances, relationships between teachers and administrators felt similarly strained.

In one case, a student shared her experience as a recent immigrant for whom English was a second language. To help in writing-based courses, the student’s parents found a writing and grammar tutor who was able to provide excellent support. When the student’s writing drastically improved, however, her teacher accused her of plagiarism and penalized her grade. The student discussed how much this affected her self-confidence and how she felt disrespected by her teacher.

“There really was not a feeling of trust, responsibility, and respect,” Elmesky recalled. With this background in place, she, Marcucci, and UCHS staff prepared to put knowledge into action. “We all said, let’s cogenerate this. Let’s do it together. Let's find a series of mechanisms that will allow us to shift the culture from one that's more punitive to one that's more restorative.”

“Let’s do it together”

With this sentiment in mind, the partnership was named “Cogenerating a Community of Trust, Respect and Shared Responsibility.” Throughout several phases over the next seven years, the project has focused on school change initiatives through restorative justice efforts, which seek to respond to conflict and disciplinary issues through understanding and cooperation.

In 2016, Elmesky and Marcucci submitted a report to the University City school district. Their recommendations were promptly translated into action, including initiating classroom “restorative circles” to encourage students to talk openly, offering an elective course on restorative justice, partnering with nonprofits to train staff in trauma-informed care, establishing mentorship programs, and hiring a restorative justice coordinator. Elmesky and Marcucci also led a summer teacher residency program on the Washington University campus where UCHS teachers developed research skills by analyzing focus group transcripts and classroom instruction videos.

“When we submitted that report to the district, I gave specific recommendations of how the school district itself could make changes, how the high school itself could make changes, and how teachers and students could make changes,” Elmesky shared. “Whenever you want transformation, you really have to go across all levels. You can't tell the teachers, ‘oh, you have to do things differently,’ if at a more macro level there's not that continuity of vision. So a lot of what we did initially was to try to establish a collaborative approach to building that vision.”

I remember that the teacher told me that it was the first time she had ever seen her students' eyes...in that small circle she felt like it was the first time she was able to connect with her class.

In some instances, Elmesky was directly involved in the transformation. She and Marcucci supported Bishop Baker, CEO of the nonprofit Man of Valor, as he led weekly student leadership programs at UCHS, piloting many of the restorative justice practices. Elmesky and Marcucci also cotaught one academic class for almost three months, dividing the classroom into three restorative circles. The smaller groups and focused time empowered the instructor and students to develop more respectful and trusting relationships. “I remember that the teacher told me that it was the first time she had ever seen her students’ eyes,” Elmesky recalled. “In that small circle she felt like it was the first time she was able to connect with her class.”

Matt Tuths, who teaches Latin and participated in Elmesky’s summer residency program, set aside the last 15 minutes of his classes to show clips of classroom videos back to his students. Students would then reflect on what was going well or not going well in class. In some cases, this opened up conversations on important but sensitive topics, like the role of race at the school, Elmesky said.

Transformative change

Catalyzed by the WashU research collaboration – and nourished through the dedicated commitment of staff, administrators, district leaders, and community partners like ABCToday – the transformation is evident. Suspensions are down by 41% and absenteeism has decreased by 7%. In 2019, the school board passed the “Resolution to Humanize School Climate Through Restorative Practices and Social Emotional Learning,” the first resolution to address student well-being, equity, and the school-to-prison pipeline in Missouri. Susan Hill, the former principal of UCHS and now the University City school district’s director of college readiness, says the shift in school culture has been drastic.

“Our school is now a more student-centered place that honors student voice and choice,” Hill said. “The relationship between the student and the teacher is more positive, in part, by being less punitive and giving students more of a voice when there's a conflict.”

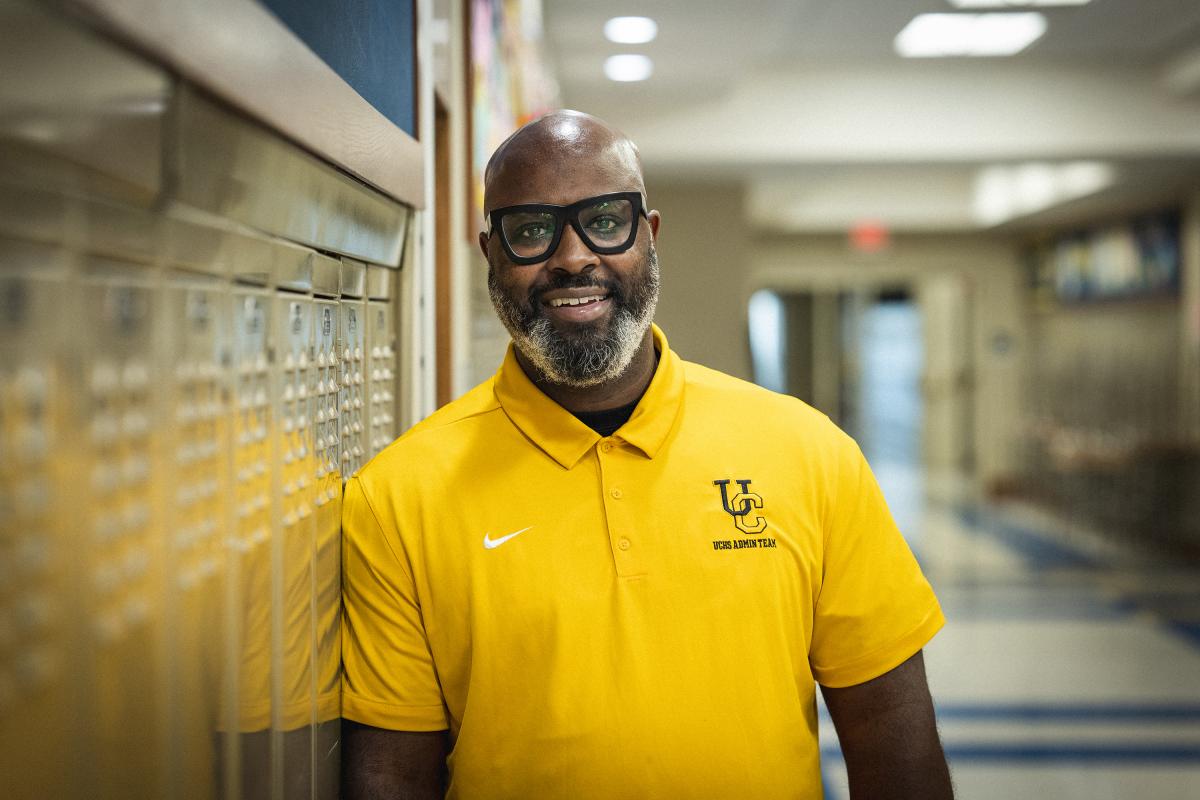

Now in its seventh year, the partnership is ongoing, ebbing and flowing as the school requests additional support, such as for identifying ways to promote student wellness in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The current principal, Michael Peoples, has carried forward and expanded the efforts.

Michael Peoples, Principal of University City High School

Elmesky describes Peoples’ leadership style as “all about relationships and socio-emotional learning.” His initiatives include ‘Lunch with the Principal,’ where he invites students who are often absent from school to a special lunch. At first students worry that they are in trouble, Elmesky said, but they soon realize that Peoples genuinely wants to know how the school can help them return to and stay in class.

“It is exciting to see the culture of our school grow healthier and healthier,” Peoples said. “Our students increasingly feel they have a voice, and that builds confidence to collectively do things to change school systems and traditions to better meet their social, emotional, and learning needs.”

Going forward, UCHS hopes to see a continued shift toward not only a restorative community with fewer disciplinary infractions, but also one with more equitable post-secondary outcomes – change that will not happen overnight. “We still have a lot of growth to do, but we would be so much further behind if it wasn't for Rowhea getting that work started,” Hill said.

The power of cogeneration

According to leaders and participants from both UCHS and WashU, the project’s success is largely due to its collaborative nature. At every step, the effort has been a true partnership.

“Rowhea’s research ethos is such that she truly views the people that we work with at University City High School as co-researchers and collaborators,” Marcucci said. “She has invested so much of her time into University City High School, not for her own ego or own research agenda, but because it is action for social justice. Anything that promotes high-quality schooling is something that she wants to invest her time in.”

Tuths, who in addition to Latin now teaches restorative justice practices at UCHS, echoed the sentiment. “Rowhea brings her own expertise to the table and wants to share that with you. But she also wants you to share the things that you bring to the table and put that all together so that we're all benefiting from each other's perspectives and expertise,” he said. “She asks you questions, and you feel like she is listening to every single word that you're saying – not just because she feels like she should, but because she actually wants to hear.”

In St. Louis, for St. Louis

discussion groups in classes throughout the school.

(Photo: University City High School)

Though some refer to education as the “great equalizer,” in reality, American schools often have limited power to combat the deep social inequities that plague the nation. Elmesky’s partnership with University City High School demonstrates how – through collaboration, trust, and true commitment – education can, in fact, be leveraged as a powerful tool for social change.

It also reflects Washington University’s increased focus on being, as Chancellor Andrew Martin has emphasized, “in St. Louis, for St. Louis.”

“Using language that says we care about the community, and we want to be part of making this better, I think is the first step,” Elmesky said. “Next, we need to continue mobilizing resources to make that vision a reality.”

Marcucci, who wrote her dissertation on this project, has continued focusing on racial justice and equity in schools as a member of the faculty at Johns Hopkins University. Looking back at her doctoral work, she sees the partnership with University City schools as an example of how universities can meaningfully interact with their neighbors. “It’s one small step in shifting how the university relates to its community,” she said, “and one that emphasizes humanity first.”