A new project from two WashU researchers uses digital text mining to examine how historical newspapers contributed to the spread of racial violence and what it means for our modern media landscape.

On September 20, 1903, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a full-page article about West Plains, Missouri, a small town 200 miles from St. Louis. The story featured a dramatic illustration of a Black man fleeing on foot. According to the article, white residents had left threatening notes in the mailboxes of many Black residents, which led them to abandon their homes, businesses, and church.

The version of the story that spread to St. Louis readers suggested that West Plains’ Black residents were permanently exiled. But reporting from the local newspaper in West Plains painted a different picture, one where many of its Black residents refused to leave, or left and eventually returned. “As far as we can tell, there was no further reporting in the Post-Dispatch and the initial, hostile, and perhaps incorrect impression was left to linger for St. Louis readers,” said Geoff Ward, professor of African and African American studies and director of the WashU & Slavery Project. “The article presented this as a humorous episode, mocking Black residents terrorized by this threatening note and spreading news of how surprisingly easy ethnic cleansing can be.”

Ward and colleague David Cunningham, chair and professor of sociology, are part of a team taking a deeper look at the media’s coverage of stories like these, analyzing them for their meaning and impact, and using digital data mining techniques to trace their spread throughout the country. The three-year project, supported by a $500,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation, will consider how this spread of information relates to the temporal and spatial diffusion of racist ideology and racial terror events, as well as its resistance.

“The work we do to understand racialized violence — how it was organized, encouraged, and often resisted — can point towards the legacies that are left for communities and how that struggle can matter today,” Cunningham said.

From Mississippi to Missouri

Cunningham and Ward met in 2007 when they were both in Mississippi to work on a truth and reconciliation project related to the legacies of the Jim Crow era. Despite working at different universities, they began to collaborate on research about the organization of racialized violence, later co-authoring several papers and co-editing two journal issues. When they later joined the faculty at WashU, they saw a chance to join forces again to deepen their work chronicling and understanding the dynamics of this type of racial aggression.

In the 15 years since the researchers first teamed up, the media landscape changed significantly. Cases of racial violence — like the killings of Philando Castile and George Floyd — are now captured by bystanders with cell phones and going viral on social media. “We think about vicarious impact, where people are traumatized by information about something rather than experiencing it directly,” Ward said. “That’s something that’s been of interest in the context of social media and police violence in the contemporary period.”

When Ward heard about the Viral Texts Project from Ryan Cordell and David Smith, he saw the potential for data mining to assist in their research. The project uses machine learning to surface information from newspaper archives. Cordell, an associate professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, along with his former colleague Smith, associate professor of computer sciences at Northeastern University, first developed it to search for reprints of literature. The technique, called vector space analysis, is adapted from the technology used for both plagiarism detection and genome sequencing. It looks for words that are repeatedly used together, creating a stronger mathematical relationship within the model. “If we can identify those relationships, that enables us to zoom in on the millions and millions of reprints we have and pull out texts that are more likely to be about the incidents we want to track,” Cordell said.

With Cordell and Smith on board as collaborators, Cunningham and Ward could focus on identifying keywords and language used to describe racial violence. For example, they pointed to the use of the word “flogging,” a lesser-known term historically used in the Midwest to describe events where Blacks were targeted for intimidation. Cordell and Smith were able to use this information to train the algorithm to find instances where this term and other examples of coded language were used in newspaper stories.

The team is hoping to focus on a particular type of racial violence, one that hasn't been widely studied. “Over the last decade or so there’s been attention given to cases of individual historical killings, but not necessarily collective violence where the whole community was intimidated,” Cunningham said. “We’re looking at lesser-known spaces, such as here in the Midwest, where we find documented chains of collective violence in which entire Black communities were targeted.”

They’ve identified a cluster of these cases, spanning the Civil War era, the Reconstruction era, and a later period focused on southern lynchings and “serial Midwest terror,” drawn primarily from incidents in Missouri and Illinois between 1884 to 1909. Their period of interest ends with the “long red summer” when racial massacres took place in East St. Louis, Illinois, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, and racialized violence erupted in dozens of other cities between 1917 and 1921.

While the team is interested in linking stories and tracing their spread, they also aim to understand the media’s approach. “We’re studying the atmosphere, the ways newspapers contributed to an environment that is more or less conducive to the rationalization of and tolerance for racial terror,” Ward said.

The team’s Mellon grant includes a commitment to turn their findings into public-facing formats, like digital exhibitions and library or museum exhibits. And, in the summers of 2024 and 2025, the project will offer an opportunity for WashU students to work as researchers through the Humanities Digital Workshop. “This is exactly the type of hands-on research opportunity we’d like to offer our undergrad and graduate students,” Cunningham said. “We are lucky to have the opportunity to do that here on campus with the workshop.”

Parsing newspapers

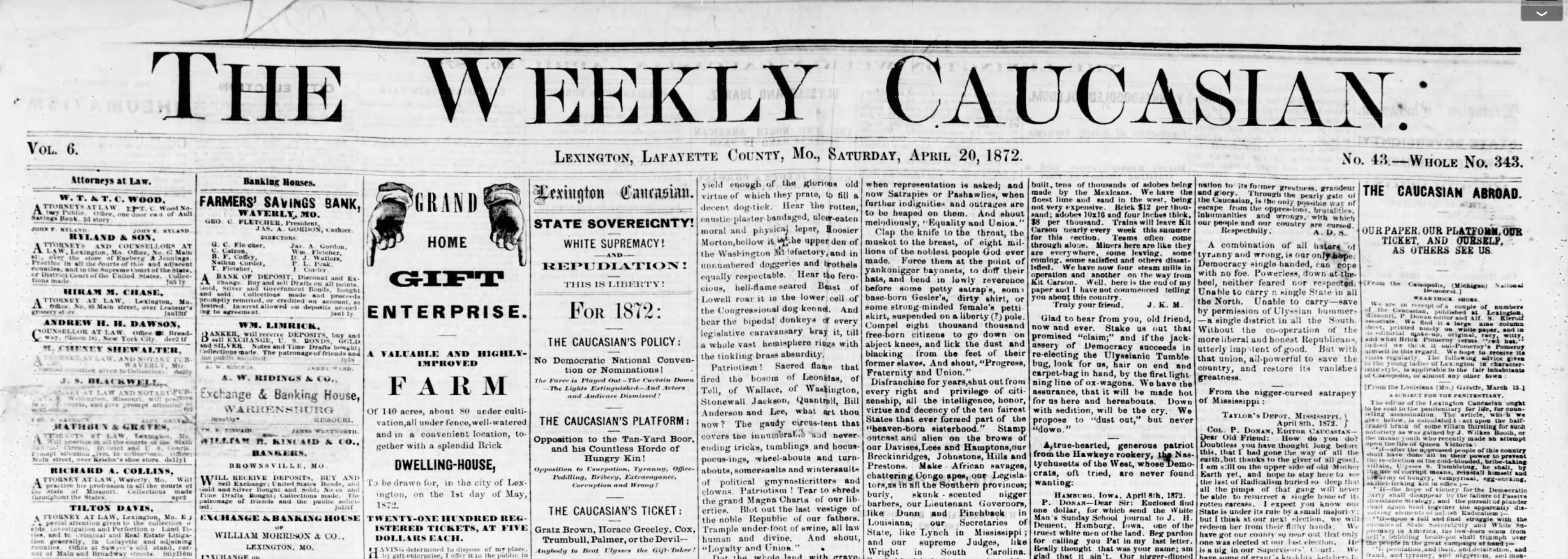

One of the team’s early findings has been a nationwide network of papers called “The Weekly Caucasian.” In addition to sharing a name, the papers shared overtly white supremacist content, Ward said. By the end of their three-year project, the team hopes to understand if this was a loose network of publications or an organized one and if the papers picked up stories from each other or worked independently.

The Black press is another important aspect of the project, and the team aims to analyze the oppositional role these papers played. Often, the narrative presented in a Black paper significantly diverged from its depiction in the white, mainstream media. Many Black papers are not digitally preserved and must be manually parsed, making for painstaking work. But Cordell and Smith’s digital text mining program is still helping the team surface key cases of interest, which allows them to comb through the Black papers on specific dates and compare coverage.

In their analysis, the researchers will have to consider historical literacy rates, since many people of the era — Black and white — were likely illiterate. Still, Ward thinks that the stories likely served to intimidate. “Just imagine a Black house servant to a white family seeing the Post-Dispatch article on West Plains sitting on a dresser,” he said. “Even without being able to read it, the imagery would have likely left an impression on a Black viewer.”

"The work we do to understand racialized violence can point towards the legacies that are left for communities and how that struggle can matter today."

The power of the press

Cunningham and Ward are interested in how the media taught communities to think about race and racialized violence. They found that white media would often invert the narrative of events, a dynamic Cunningham said continues today. “The victims in question would be the Black community, but related media accounts would typically emphasize alleged prior victimization in the white community, with racist mob violence framed as a reaction to that,” Cunningham said. “That kind of coverage matters not only because of what it depicts, but also based on its intentionally inflammatory function. Recognizing that could offer a narrative lens through which people understand the tensions they may see in their own communities.”

Newspaper stories were often used to reinforce the relationships of dominance and subordination between Black and white citizens, Ward said. The team is tracing one story about several Black residents in Elsberry, Missouri, who were beaten on the courthouse steps. “The evident impunity for those perpetrators told all the Black residents of the town — and people wherever the story reached — that there were limits to human and civil rights,” Ward said. “It was meant to have a chilling effect, discouraging political action, economic activity, and any kind of organizing. It also legitimized further political violence.”

Ward also pointed to the way certain towns used media coverage of outside events to justify racial violence on their own streets. Take the East St. Louis massacre of 1917, he said. “After the event there, East St. Louis media were more dismissive or enabling of racial violence elsewhere, as if to communicate, ‘Hey we aren’t so bad, others are doing this too,’” Ward said.

Holding media companies accountable

Though information may travel more quickly today, Cunningham said traditional media have always had the power to spread messages and ideas across vast distances. “We frequently speak of racism having a systemic character. One aspect of this relates to how racialized violence can be linked across places that aren’t necessarily geographically close,” he said. “We can interrogate how the manner in which an event that occurs in one place is not wholly independent of something that occurred a thousand miles away and two months prior.” Cunningham believes this understanding can be helpful as communities seek to memorialize and reckon with their pasts.

While the project’s primary focus is historical, it will also consider the spread of white supremacist ideologies in contemporary viral media like Twitter and Reddit. “Public writing and exhibitions will connect this historical research to these contemporary contexts,” they said, “contributing to information literacy and efforts to understand, link, and address historical and contemporary cases of racialized political violence in the U.S.”

Ward said contemporary media have a responsibility to consider how they frame stories of racial violence. (Some news organizations, including the Baltimore Sun, have already started the atonement process, he added.) As part of the project, Ward wants to map all of the places that reported on the 1898 Wilmington, North Carolina, massacre; the 1917 East St. Louis massacre; as well as other atrocities, to see where it was condemned and where it was written about apologetically or dismissively.

“That visual will be telling in terms of how our newspapers and their holding companies are implicated in this history,” he said. “Some newspapers created an environment that was conducive to racialized violence. I think we’ll be able to go to those institutions and ask, ‘What can you do to atone for this?’”