Historical perspectives differ not only from culture to culture but also across our own Danforth Campus. Physicist Brendan Haas and historian Joohee Suh each explain how their research grapples with "old" subject matter.

From the Department of History to the Department of Physics, history is organized through vastly different symbolic tools, research methods, and intervals of time. We sat down with a graduate student from each of these departments to discuss their unique approaches to understanding history.

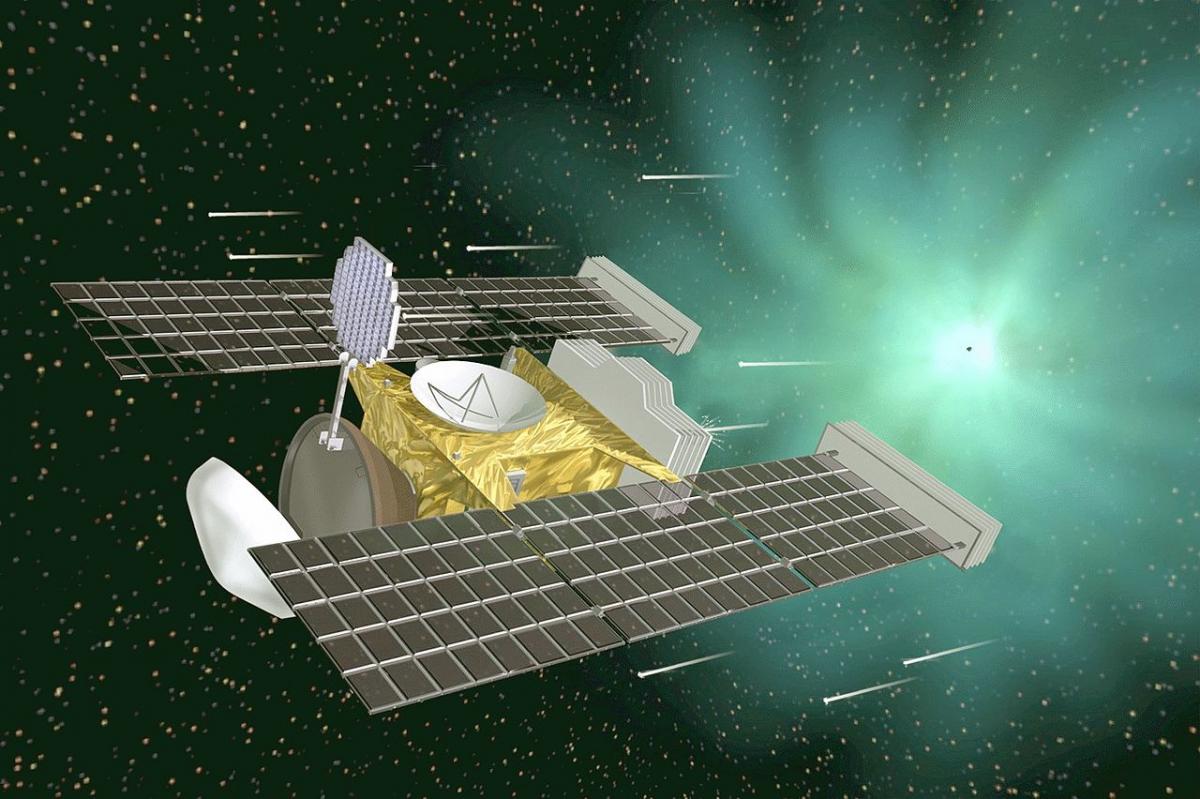

Peeking into the solar system’s origins

Back in 2006, a NASA spacecraft hurtled through the cloud of debris surrounding the comet Wild 2. Moving at a relative speed of 6.1 kilometers per second, a grid of aerogels and aluminum foils collected as much of the debris as possible from Wild 2's coma, the atmosphere of gases and particles surrounding the comet. Now Brendan Haas, a PhD candidate in the Department of Physics, is studying these aluminum foils and the dust particles that hit them. “By investigating comets we are hoping to learn more about possible transportation processes in the early solar system,” said Haas.

Comets like Wild 2 have spent much of their lives in the cold outer solar system since their birth billions of years ago (more than 4.5 billion in the case of Wild 2). Studying comet debris is like looking at fossil remnants in a rock here on Earth, except Haas doesn’t look at skeletal remains, he looks closely at the elements that make up the sample.

The history of the universe has always been on Haas’s mind. After graduating from the University of Chicago in 2011, he worked on an essential component of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland the year the elusive Higgs boson was discovered. And although he was helping recreate the conditions of the Big Bang, he yearned to be more directly involved in the research. So, instead of briefly glimpsing a tiny snapshot of the early universe, Haas decided to join the Laboratory for Space Sciences here at WashU to hold remnants of the early solar system in his hand.

“I thought it was very cool that this lab does astrophysics with a microscope instead of a telescope,” Haas explained. “The sample is physically there. It makes me feel more involved in my research.” Although the samples were heavily altered from their original form after being captured by the spacecraft, their elemental composition is still intact – though not the composition Haas expected.

Since comets are found in the outer reaches of the solar system, they are icy, and not just water icy. Their temperatures are so low that elements we think of as gaseous, such as carbon dioxide and methane, are frozen solid. Analyzing his samples from the Wild 2 comet, Haas found something else. “We’ve seen materials such as calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions that could have only formed in high-temperature environments. How exactly that is occurring is still poorly understood,” he said. Along with this, Haas and fellow researchers identified chemical compositions more closely associated with meteoroids, rocky bodies that orbit much nearer to the sun. These discoveries have put the standard model of solar system history in doubt – a model that has become more and more shaky in the past few decades.

This kind of uncertainty is common across all disciplines. Old paradigms topple and new rough drafts fill the spaces. Haas’s work is another voice in the grand narrative that is our solar system’s history, inserting a comment where appropriate amongst the many other voices within the discipline.

Chinese burials and the history of the body

Millions of kilometers and billions of years away, in 18th- and 19th-century China, the Qing Dynasty had a problem: People weren’t burying their dead. The overcrowding that had accompanied the Early Modern period had created a shortage of affordable burial sites. Since cremation was thought to be disrespectful to the dead, many people left the bodies of their loved ones unburied, hoping that they would be able to afford to give them a proper burial at a later date, which, as you might imagine, created some serious health concerns. Joohee Suh, a PhD candidate in history, has been studying this problem and what it can tell us not only about how people living over 200 years ago treated the dead, but how they felt about the human body more generally.

Suh is interested in a subfield known as the History of the Body, which presents the body as a unique subject of historical inquiry. Much of the scholarship on the history of the body comes from European scholars, who primarily use medical texts to discover what people in past centuries thought about the body.

Suh explains, “During the Early Modern period after the Renaissance, people begin to understand the human body differently, and they begin to use the human body differently” through the development of medical knowledge. This way of gleaning the history of the body through medical texts has proven not to be as applicable in China, however. “China didn’t have any kind of similar medicalization during the Early Modern period, so I had to find some other way to access these dead body problems.”

To learn more about what people thought about the human body, in particular the dead body and its value, Suh has investigated a number of historical archives at the Academia Sinica in Taiwan, the Grand Secretariat Archive preserved from Qing government in 18th and 19th centuries, the Palace Museum in Taiwan, and the First Historical Archives of China in Beijing, but the picture she can glean from these sources is necessarily fragmented and incomplete. A couple centuries might not seem like much when compared to the long history of the solar system, but reaching back even this far has its challenges, particularly when it comes to determining what regular people thought.

Although there are written records from the Qing Dynasty, these accounts are written from a particular viewpoint and only give a partial view of the problem. Like Haas’s dust particles, which he can access only after they have been altered by a violent impact with the spacecraft, Suh has no access to an unaltered, unfiltered record of what happened during the Qing Dynasty. She, like Haas, must piece together what happened in the past based on partial materials.

“The sources I rely on are mostly from the government or written by the elites or charities. These sources talk about why people leave bodies without burial, but their perspective is always shaped by their own agenda, their own moral or ethical or practical agenda. We don’t really get to know the story of the people who actually had to leave the body unburied, because people didn’t really record those things because they were not really proud of it.”

Like Haas’s work, Suh’s research challenges current models of what we think we know about the past, but also marks the limitations of what we can know. Their work collectively shows the limits of what we are able to reconstruct about the past, and that there is always something new to discover.