A new book edited by Abram Van Engen reevaluates the historical context of Puritan literature.

When the Mayflower landed 400 years ago, in 1620, the Pilgrims on board did not consider themselves to be establishing a new country. That idea would become more prominent as the United States came into being and searched for a founding mythology.

Looking past that mythology is the subject of a new book co-edited by Abram Van Engen, associate professor of English at Washington University, and Kristina Bross. A History of American Puritan Literature (Cambridge University Press) resituates Pilgrim and Puritan literature within the historical context of the 17th-century Atlantic world, arguing that it is impossible to understand what Puritans were doing in this period without first considering their participation in colonial systems.

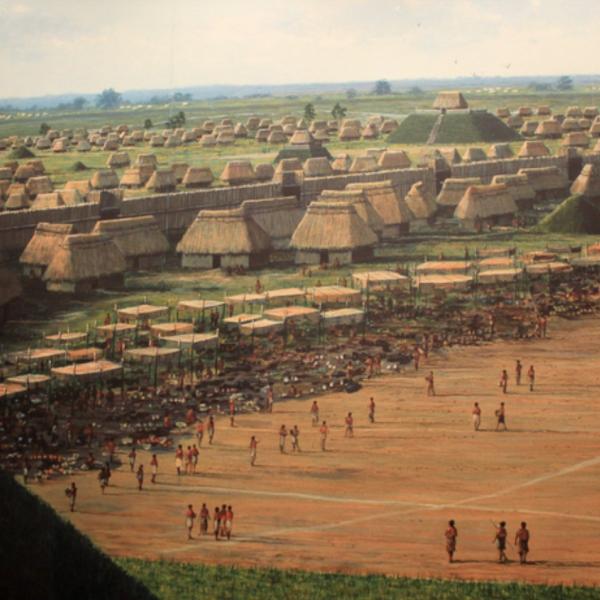

Puritans were never isolated in America. They took part in the Atlantic slave trade and had close economic relationships with both England and the Caribbean. As colonial settlers, they had a complicated and often violent relationship with Native peoples. They came with an ideal of restoring the church to its original purity, Van Engen argues, but they did not come to the Americas with the intention of starting a new nation or setting themselves apart from the world.

“The Puritans did not come here with a sense of themselves as particularly exceptional, and certainly not with a sense of America as particularly exceptional,” said Van Engen.

His latest work builds on a book published last spring, City on the Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism, in which Van Engen argues that Pilgrims and Puritans are often used to illustrate a simplified version of the history of European imperialism. New nations require origin stories, founding myths that explain what makes them unique on the global stage.

“The Pilgrims and the Puritans have featured in those stories about United States’ national origins because starting with the Pilgrims enables us to tell a story of the nation that's all about liberty and not about slavery,” Van Engen said.

Despite this cultural legend, the Pilgrims and Puritans were directly involved in the slave trade. The language of liberty was very important to them, but it was a specific kind of liberty they pursued. New England was still not the land of the free, as it was later portrayed to be. Slavery existed in the north as well as in the south, and the slave trade was enormously important to New England’s economy.

“The Pilgrims and Puritans are fascinating,” Van Engen said, “but when we celebrate them as the people who came here for freedom, we lose sight of the unfreedom that they also caused.”

A History of American Puritan Literature refocuses the scholarly conversation on the complex relationships Puritan writers had with their historical moment. When Van Engen teaches Puritan literature, he often begins with an explanation of the differences between Pilgrims and Puritans. Blurring the line between those groups is often part of the American mythologizing of that period.

The Pilgrims separated from the Church of England and fled to the Netherlands because of religious persecution in England. They boarded the Mayflower, not because of continuing religious troubles in the Netherlands, but because of the economic hardships they faced there.

“Pilgrims and Puritans get blended into one big origin story, when in fact they are different peoples with different colonies, patents, and perspectives.”

The Puritans, however, came to the Americas a decade later, in greater numbers, and with far more institutional resources at their disposal. Whereas 102 Pilgrims came over on the Mayflower, 1,000 Puritans came to Boston. Unlike the Pilgrims, the Puritans had an official charter from the King of England to establish a colony and had not separated from the Church of England.

“Pilgrims and Puritans get blended into one big origin story,” Van Engen explained, “when in fact they are different peoples with different colonies, patents, and perspectives.”

The political and religious diversity of these early English settlers is reflected in the kinds of literature they produced. Both Pilgrims and Puritans wrote poetry, sermons, diaries, and autobiographies. Many of them were literate, including women. Their culture was book-centric. Within ten years of landing in Boston, the Puritans had founded a printing press and a college (Harvard).

By exploring the artistic qualities of Puritan literature, Van Engen and Bross aim to help readers understand the relationship between Puritan thinking and its political context. For example, Puritans had unusual ideas about what the world would look like after Christ returned. An obsession with how and when the world would end led them to write narratives that today might be classified almost as science fiction—speculative fiction with real-world stakes. They speculated about whether race exists in heaven, for example, and came to the conclusion that the various races of the world would not be segregated in the new Eden.

Weighing historical context against art, A History of American Puritan Literature provides a more nuanced picture of Pilgrims and Puritans than the one familiar to many Americans from school plays about the first Thanksgiving. With so much of the legacy of American origin stories being reevaluated today, Van Engen and Bross want to topple the idea of Puritans as the spiritual founders of the United States while drawing attention to what makes them still so much worth studying.

“We want to resituate them as not an isolated, exceptional origin story,” Van Engen said, “but instead as a complex and fascinating people in relation to others at all times.”

Read more about Abram Van Engen’s work on his website.