Rebecca Messbarger, professor of Italian and founding director of the Medical Humanities program, discusses examples of social distancing from medieval Florence to Progressive Era St. Louis.

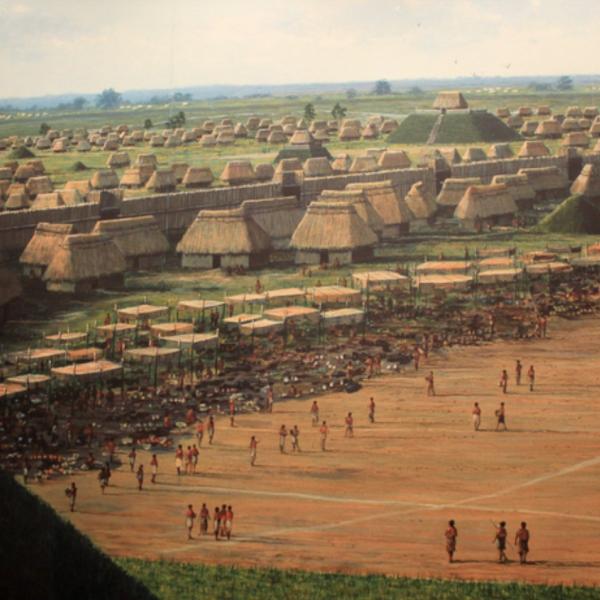

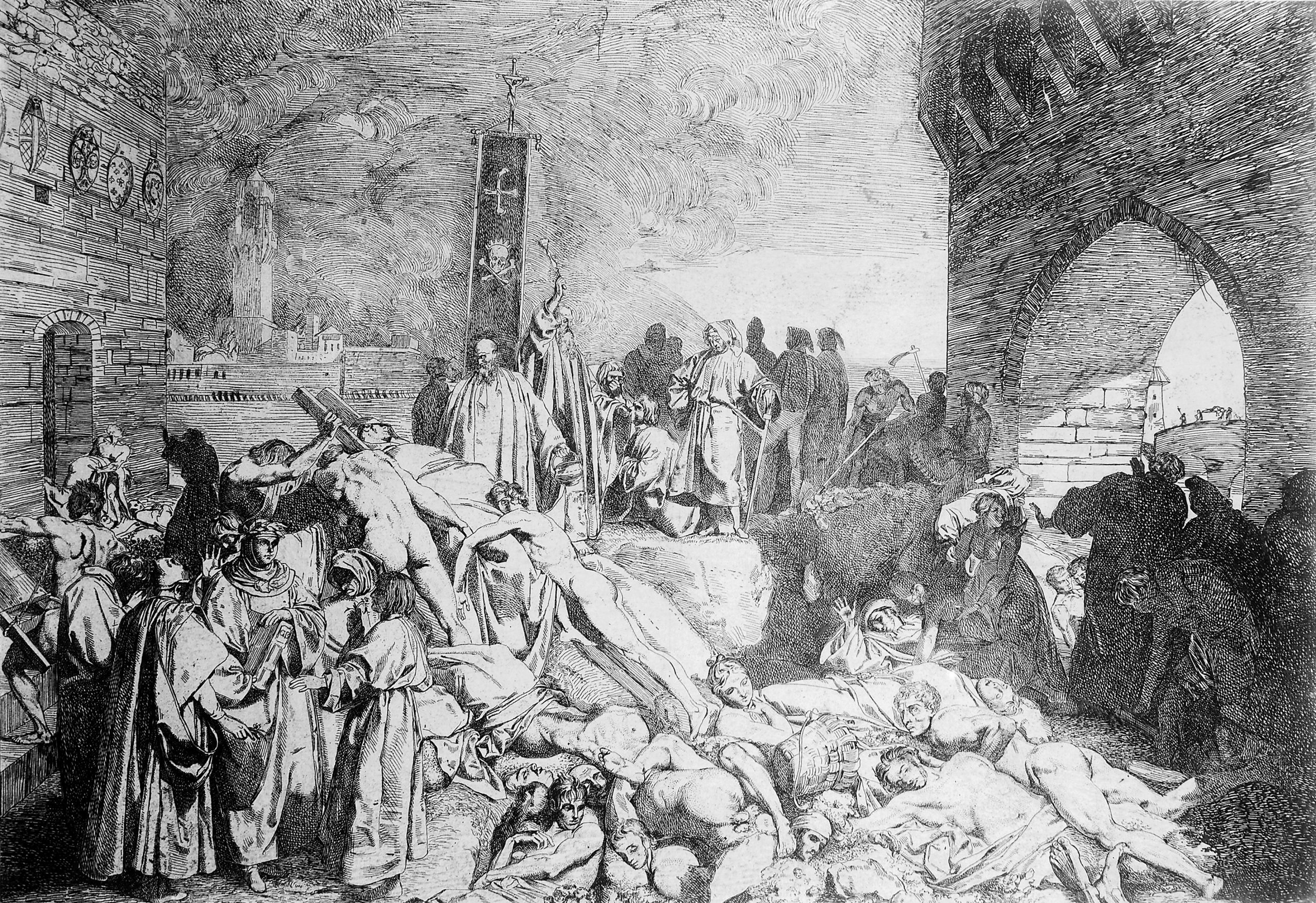

In Giovanni Boccaccio’s “Decameron,” 10 young Florentines share humorous, bawdy and heartrending tales while fleeing the bubonic plague of 1348, which devastated their city and killed one-third to one-half the population of Europe.

Now considered a masterpiece of Italian literature, the “Decameron” also represents “one of the oldest and most celebrated examples of social distancing,” said Rebecca Messbarger, professor of Italian and founding director of the Medical Humanities program in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “With the economic means to leave the contagion and death behind, they retreat to a country villa, where they gather daily in the shade to tell stories in order to forget the ills of the world until it is finally safe to return home.

“Social distancing is a term we are hearing a great deal about,” continued Messbarger, who teaches the course “Disease, Madness, and Death Italian Style.” “Past pandemics and the present COVID-19 show that the practice can save lives by limiting the spread of infection and by keeping the medical system from becoming inundated by the very ill.

“One hundred years ago, the Spanish Influenza pandemic provided evidence still studied today of the benefits of social distancing during a mass contagion. St. Louis, then the fourth-largest city in the United States, exemplified effective public health policies that limited causalities among the local citizenry far better than other cities of equal or greater size through the stringent enforcement of social distancing: the extended closure of schools, churches, cinemas, restaurants, bars, and other venues for social gathering; limitations on businesses’ hours of operation; and strict regulation of all public assembly.

“St. Louis’s iron-spined health commissioner, Max Starkloff, withstood immense pressure from the business community, school administrators and the Archbishop to enforce weeks of closures. He had the indispensable support of Mayor Henry Kiel and backup from hospital administrators and medical practitioners on the frontlines. Despite vocal opposition to the shutdowns, especially in the early days of flu’s spread in St. Louis, Starkloff built a coalition of support through public hearings and an emphasis on truth and transparency about the disease, which allowed him successfully to compel mass social distancing.

“We are seeing in real time the profound impact on communities — here in St. Louis, across the country and the globe — of implementing or failing to implement not only social distancing strategies, but timely and transparent public communication and institutional coalition-building in the face of this crisis.

“As our medieval Florentine patricians remind us, however, the ability to retreat safely and happily from the world is the privilege of a select few,” Messbarger concluded. “How government and health policy administrators mitigate the hardship many will feel over this social distancing is a critical question for our time.”

This article originally appeared on The Source.