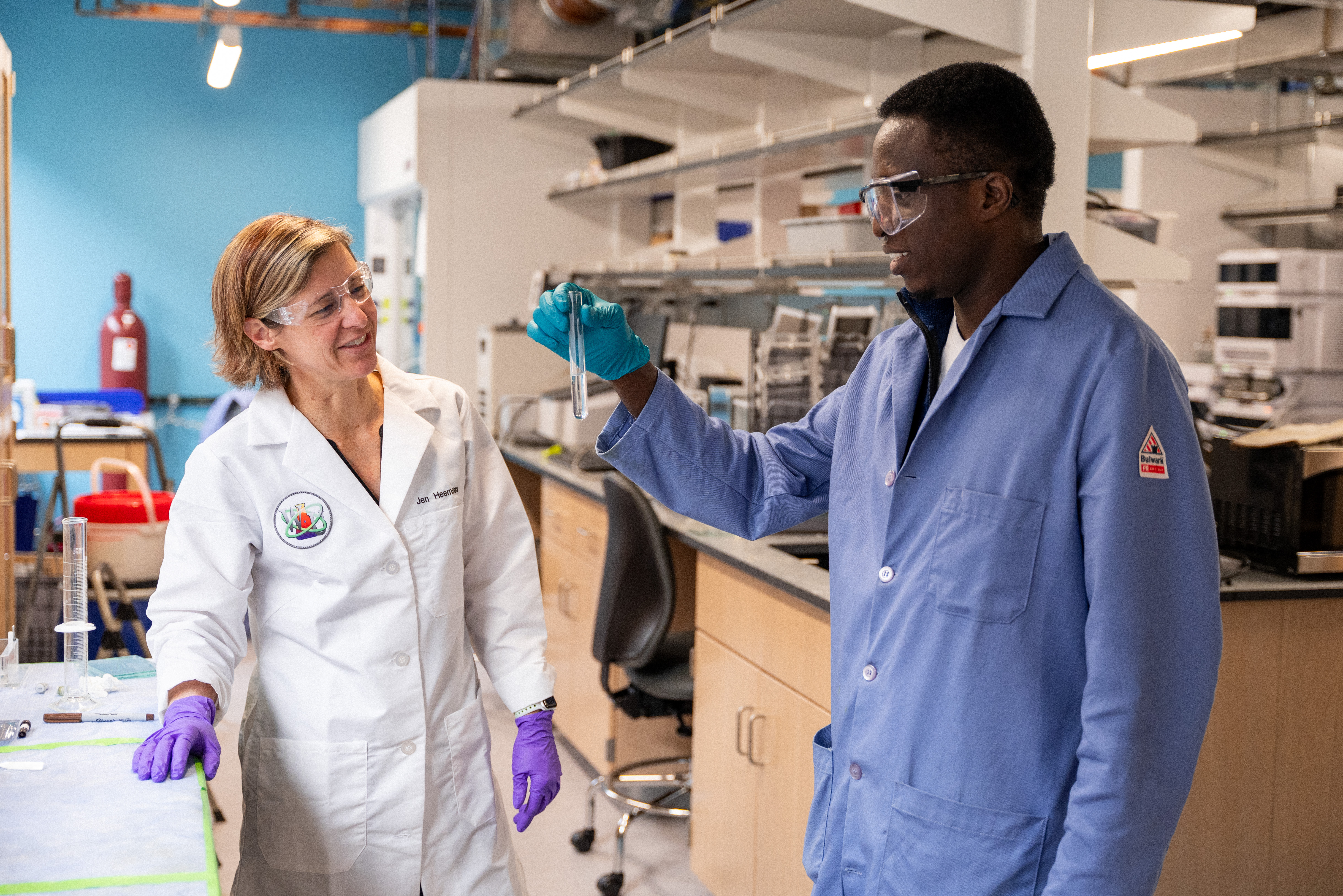

Chemistry chair Jennifer Heemstra is part of a national consortium of scientists and students charting a path for inclusive science.

As part of her ongoing commitment to improving the culture of science, Jennifer Heemstra, the Charles Allen Thomas Professor of Chemistry, has joined a national consortium of university faculty, postdocs, and students to develop a blueprint for promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in science labs.

Heemstra and co-authors — including project organizers Sandra Murray of the University at Buffalo and Antentor Hinton Jr. of Vanderbilt University — outlined their ideas in the journal Molecular Cell.

The WashU chemistry department chair currently leads a diverse lab of 16 students and postdoctoral researchers from the U.S., Europe, Asia, and Africa. She said science needs to be more welcoming to people of all backgrounds. “The best science will happen when we create a culture in academia where everyone feels supported and has the opportunity to thrive,” she said.

While Heemstra would like to see lab leaders embrace DEI for its ethical merits, she and her co-authors emphasized diversity can also spur better ideas and promote productivity. “When you have a diverse team with a wide range of viewpoints, it can be a little bit uncomfortable at first. Everyone has to think harder about their ideas and try to justify them,” Heemstra said. “Diverse teams perform better.”

The consortium outlined more than a dozen steps leaders could take to boost inclusion and opportunities in their labs. One example involved promoting postdocs or students to “sub-leaders” in charge of journal sessions or other lab activities. This approach, they wrote, should help create a “positive, supportive environment that fosters collaboration, innovation, and interdependence, thereby improving the quality of research and advancing scientific knowledge.”

The report also emphasized the importance of open communication. Lab directors should ensure trainees know they can ask questions about any process or procedure. Students, especially those from underrepresented groups, may feel uncomfortable asking questions, Heemstra said. When the lines of communication are unclear, they might miss out on important guidance and opportunities.

But Heemstra and co-authors also stressed this communication must go both ways. Lab leaders, they write, should also provide regular feedback to students. “Students may be quietly wondering if they belong here, and this is amplified for those who don’t see their identities well-represented in our community,” she said. “The metrics of success in academic research can be vague, leaving students not knowing whether they’re knocking it out of the park or on the verge of failing. That’s a huge stressor and a huge source of anxiety.”

The consortium also urged lab leaders to promote work-life balance. Scientists need a chance to relax and live lives outside of the lab, Heemstra said. Establishing a good balance can protect mental health and open the door to people with family obligations or other duties.

The consortium’s DEI guidance targeted lab leaders because they set the tone for the entire group, said Heemstra, who is currently writing a book to help scientists run labs. Scientists are often well-trained to run experiments and publish papers, she said, but they don’t always learn how to be good mentors and leaders. As a result, they often end up emulating their supervisors — for better or worse.

Most principal investigators likely want to build a supportive lab environment and are hungry for more tools and guidance, Heemstra said. “We can feel overburdened and overwhelmed. We've got 100 emails to respond to, have to keep our lab funded, and have to get papers out the door. Often we just don't know where to start when it comes to being better in how we lead and mentor.”

Heemstra tries to model open communication practices in her WashU lab. She makes a concerted effort to ensure all students receive vital advice about their development and future careers. “I was concerned that I was telling some people the same things multiple times while others were never hearing it,” she said. Now she includes career development advice in weekly group meetings.

The chemistry chair is also working with researchers at WashU and beyond to foster mentorship. In collaboration with Neil Garg at the University of California, Los Angeles, she created #MentorFirst, an initiative to promote “best mentoring practices that foster individual growth and research success.”

As part of this initiative, about a dozen researchers across WashU began gathering last fall to discuss their experiences and how to improve as mentors. In 2024, a cohort focused on researchers in the McKelvey School of Engineering will start discussions of their own. “That’s one of the fantastic things about being at WashU,” Heemstra said. “I’m at an institution that cares about mentoring and supports efforts to create tangible change.”