In a new book, Diana Montaño explores the everyday uses and adaptations of technology from the ground up.

At the start of graduate school, Diana Montaño was in the enviable position of already having not only a novel research topic but also access to a previously untapped trove of documents – the newly established archives of the Compañía Luz y Fuerza del Centro. A year later, however, the Mexican government intervened in the company and laid off many of its workers. The materials in that archive remained unavailable to Montaño as an ongoing lawsuit related to the government layoffs prevented public access.

“I’m now glad that I had to shift my research elsewhere,” Montaño, assistant professor of history, said. “If I had just concentrated on the papers from the company, I would have written a very different book, and a boring one at that.”

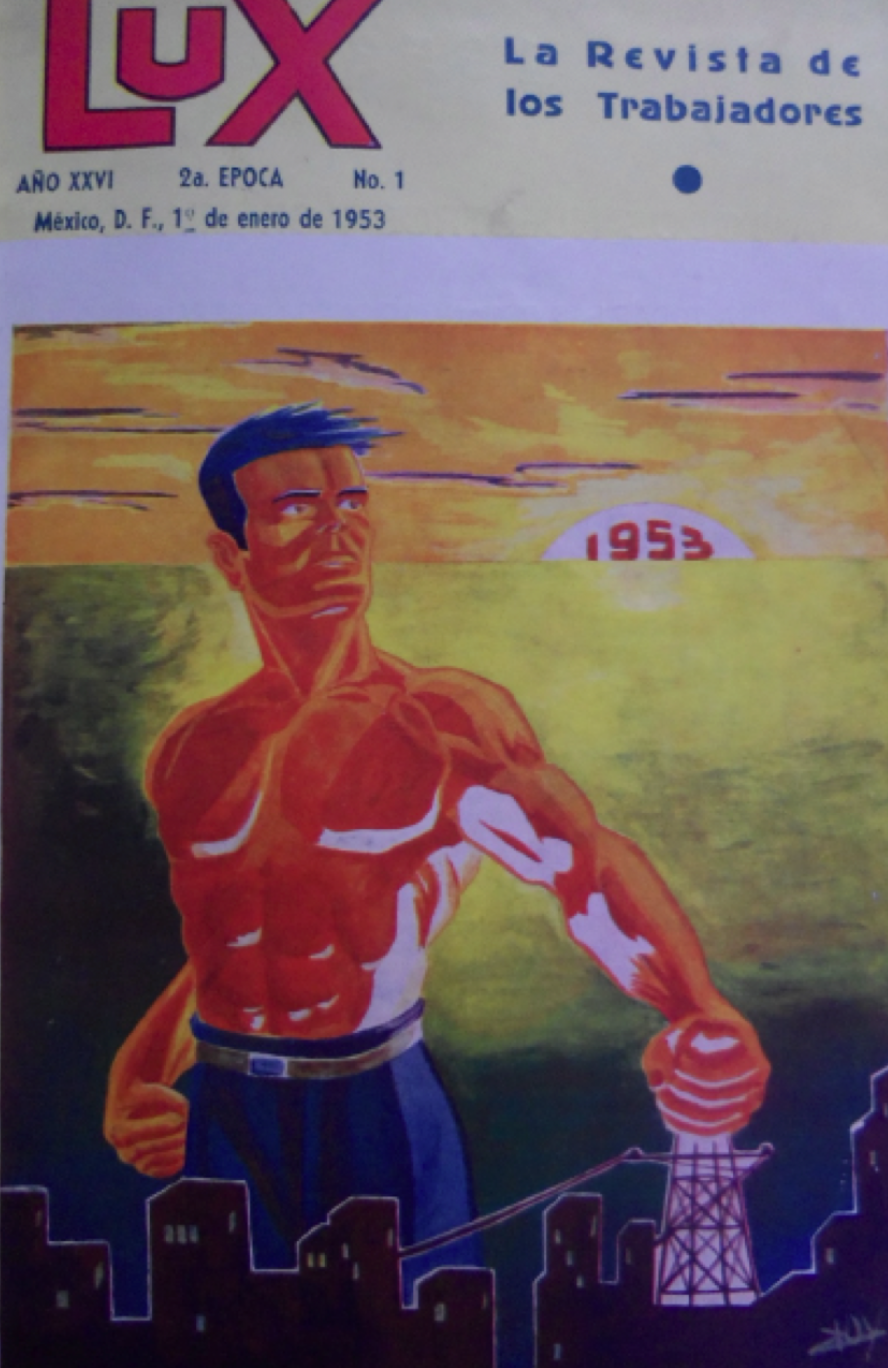

In Electrifying Mexico: Technology and the Transformation of a Modern City (University of Texas Press), Montaño explores the making of electrified spaces and how people led that electrification and then navigated those emerging spaces. She writes about the experience of electricity through lighting, public celebrations, streetcar accidents, power theft, electrical appliances, and the nationalization of the electrical industry.

Montaño is interested in what she terms “grounded analysis.” Like electrical wiring is grounded as it comes into a home, she wanted to focus her work on the perspectives of users of electricity on the ground. According to Montaño, historians often present technology as fixed entities that change society and culture in irresistible ways. She argues that that perspective removes people and their ambitions in how they employ technologies.

Grounding her analysis in everyday life also allowed Montaño to tell previously overlooked stories. “By privileging innovation and the dispersal of technologies from the North Atlantic into the Global South, historians of technology often ignore adaptation and everyday use,” she noted.

Montaño’s archive includes surprising source material, like court cases of streetcar accidents and cookbooks. In a historical methods course, she uses cookbooks as an example of how to read the lives of women through the books that they wrote. The authors of these cookbooks shaped the sale of electricity through their writing, leading electrical appliances to become markers of social status for middle-class wives.

A key theme in Electrifying Mexico is the way that everyday use created markets for techniques and knowledge that challenge the narratives of technological innovation emerging solely from places like the United States. As access to electricity increased, so did power theft. People began to market their skills outside of legal channels. Electrical workers would install illegal power theft devices on the side. Policing this theft was difficult because of how easy it was to take down and reestablish electrical connections.

“If you take a device down,” Montaño noted, “within minutes they’ll be back up. The story of power theft in this period is not the story of a single device or innovation, but the way that the ability to siphon off electricity created a market for techniques knowledge that were shared outside of laboratories.”

Montaño plans to continue researching the uses of electrification in future projects, mapping what she calls the “electriscape” of physical and symbolic elements throughout the Global South. She is particularly interested in the ways that electrification was promoted as a medical cure for various ailments.

“Once you start looking at electricity on the ground, there’s a lot there. I could have written so many more chapters.”