Next year marks the 200th anniversary of the classic novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley, which first gave life to “the monster,” now an icon in his own right. The story can perhaps credit some of its long-lived popularity to the fact that it intersects with many fields of study: literature, biology, ethics, sociology, media studies and … earth science?

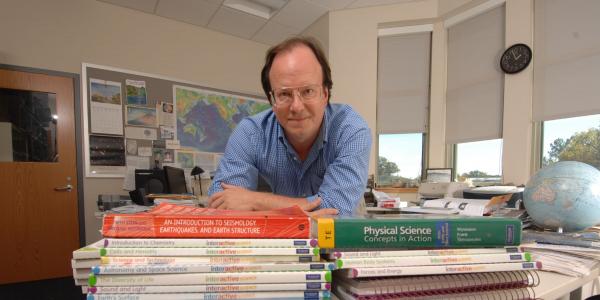

“I’ve always been a fan of the book,” admits Michael Wysession, a professor of earth and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. He read Frankenstein for the first time in middle school. “I was really into the whole genre. It was a big part of my adolescence.”

When WashU began to consider the many ties the book has across the university in order to celebrate the novel’s anniversary, Wysession was quick to point out the influences and parallels with his field, including how the book came to be, it’s setting and how Shelley’s ideas dovetail with the larger issue of climate change today. (Just a warning — there are some spoilers ahead for those unfamiliar with the novel.)

If you like Frankenstein, thank a volcano

We likely have earth sciences — and more specifically Mount Tambora — to thank for the novel’s creation at all. In 1816, the year the book was written, 18-year-old Mary Godwin had a bit of a reputation. She had an affair and a child out of wedlock with a married man (later her husband Percy Shelley). That summer, she and Shelley went on vacation with Lord Byron and writer-physician John Polidori to Geneva, but the weather was terrible. Gloomy, dark, rainy and cold, the group of writers decided to have a competition to see who could write the best horror story. Mary wrote Frankenstein. So how does this involve a volcano?

The eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in 1815 was the largest volcano eruption in the last several centuries. “There were a lot of sulfate aerosol particulates ejected into the atmosphere, and this blocks out some sunlight and causes temperatures to drop,” Wysession says. “We didn’t have satellites and computer technology at that time, so we couldn’t quantify it. But with smaller volcanic eruptions, such as Mount Pinatubo in 1991, we saw the global temperatures drop more than a degree over the next year, even in spite of the El Niño at that time, which normally drives temperatures upward.

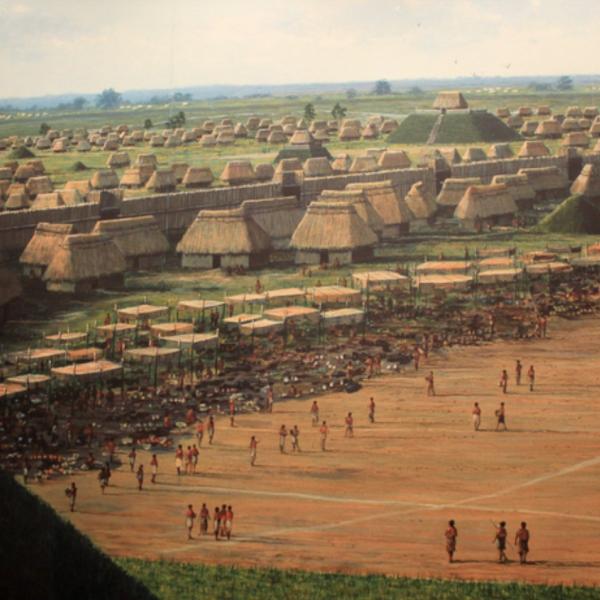

“The following year, 1816, was known as ‘The Year Without Summer,’” Wysession continues. “The climate in the eastern United States was just devastating. Crops failed, the winter rains were freezing, it snowed in the summer; there was mass starvation. Whole towns in New England actually decided to pack up and leave, causing a mass exodus south and westward.” Though the Louisiana Purchase was made in 1803, it wasn’t until this time that the first large migration began. So this volcano in Indonesia played an important role in the settling of the United States.

But back to Mary Shelley. “Europe was also devastated. Temperatures were several degrees colder on average. It was cold, bleak and rainy, and there was massive flooding,” Wysession says. In fact, the flooding inspired many European governments to found their first national scientific organizations to study meteorology in order to better predict such floods in the future. “It was a dismal time, and I think that led to a feeling of gloom and pessimism that year throughout Europe, which was particularly hard hit. It was the perfect atmosphere for dreaming up Frankenstein.”

Leave a Comment:

0 Comments