Benson discusses what it means to be a Black, Southern ecopoet — and the youngest-ever winner of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize.

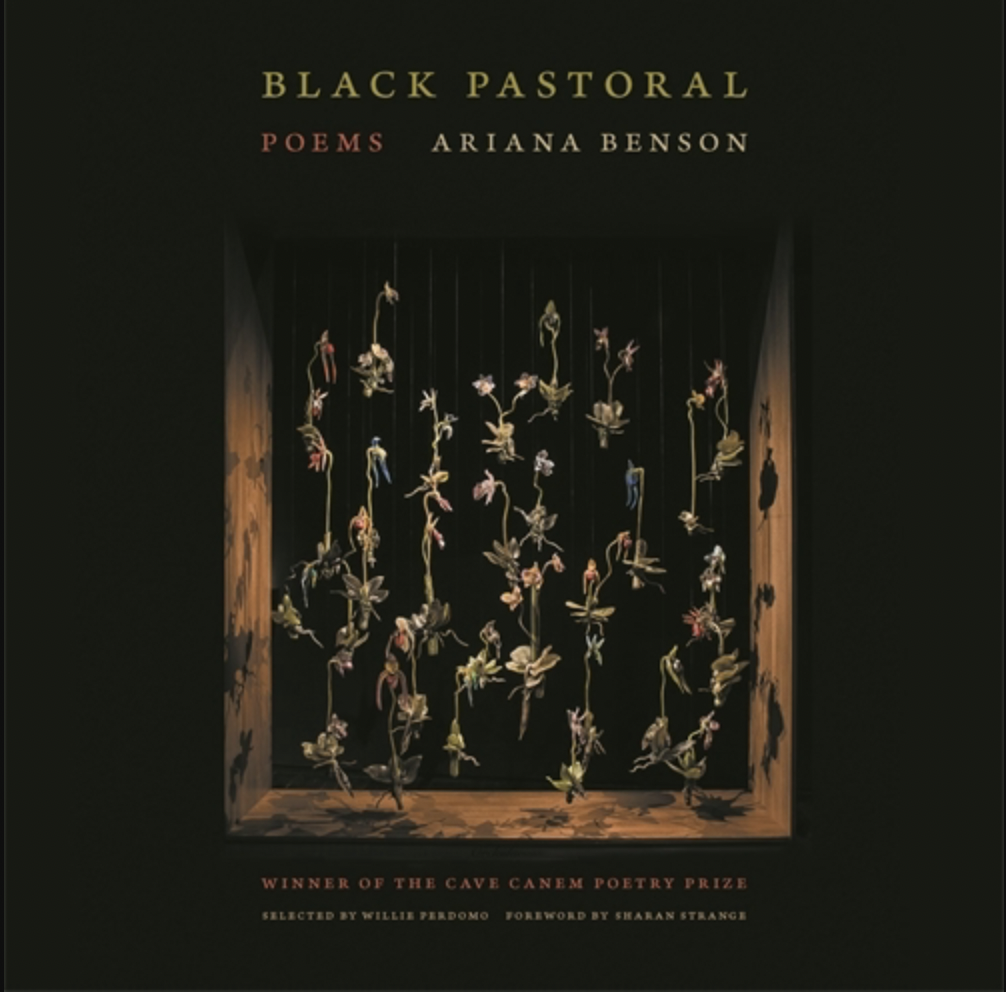

Ariana Benson, a second-year student in the English MFA program, will publish her first poetry collection “Black Pastoral” in September. She wrote much of the collection during COVID when the pandemic compelled her to leave London, where she’d been studying poetic practice as a Marshall Scholar. Returning to her hometown of Chesapeake, Virginia, gave her the time, as well as the landscapes, to spark inspiration. Her collection — rooted in Black history, memory, and nature — has already gained national recognition, winning the Furious Flower Prize and the Cave Canem Poetry Prize. She sat down with the Ampersand to talk about her work.

How did you become a poet?

Poetry chose me. I’m passionate about storytelling, and poetry is the medium that most appeals to me because of its ability to balance lyrical sensibility with emotion. During COVID, which was the first time I wasn’t in school, I went back to Virginia, which is a really storied land. I grew up near the Great Dismal Swamp, a place where enslaved peoples escaped and built maroon colonies. It’s this mythical place that shaped how I engage with the landscape and the environment.

One day, I was driving to my grandmother’s house on the Moses Grandy Trail, a road I’d been down many times in my life. I googled the story of Moses Grandy and came across his personal narrative, that of an enslaved man who carved out the canals in the Dismal Swamp. This plunged me into the history of this land, and I felt there was no way to tell the full range of the story — not just the facts, but the affect — without poetry. So, I ended up writing a love letter from the swamp to Moses Grandy.

Poetry allows for an extra layer of seeing. I hope that through writing poetry and telling the stories at the heart of these headlines, I’m expanding readers’ ability to have compassion and empathy, and to explore what they’re overlooking in themselves. Instead of the plain facts of life, it’s about seeing life as a beautiful ball of grief and joy and happiness and love.

You've been described as an “ecopoet.” What does that term mean to you?

When I was a kid, I was what you’d call a “tree climber.” I’ve always had a connection to ecology and nature. I find that every poem I write touches on ideas of ecology, landscape, and environment. It’s not something intentional; It’s how I see the world. But there might be a better label, like “historical-eco.” I’m obsessed with memory, and I don’t think you can separate the two. When I see a landscape, I always ask the question, “What happened before I was here?”

Fundamentally, I want to understand how the things we remember — or the things the people who came before us remember — shape the world now. I feel very strongly about the dearth of Black stories in the archive. I also try to take stories where the facts are widely known — like the story of Mildred and Richard Loving — and map affect and emotion onto them so they seal in peoples’ minds.

Willie Perdomo, the judge who awarded the Cave Canem Prize, wrote that your work forces the reader to “de-romanticize” the landscape. How do you square that with being an eco-poet who finds beauty and meaning in the environment?

As much as I love nature and have distinct reverence for it, as a Black American, I grate on the lack of confrontation with all of the things that happened on the beautiful land. I’m never going to look at a tree and just see a tree. There’s an underlying darkness there.

Bringing that out was a goal in “Black Pastoral.” It’s about the pastoral landscape and the beauty of it, but “Black” has a lot of multifaceted meanings. It’s not just referring to my identity and culture, but also to that painful history that is in the landscape of the American South. I would agree that I’m de-romanticizing it, but hopefully in a way that allows readers to fall in love with the truth of it all over again.

Does revisiting these dark themes in your work take a toll?

Yes, and I do have to take breaks from it. I would say that I often write poems that get into the uglier parts of history in quick succession. So, I’ll spend time in that place for a while but then I’ll allow myself to write a poem about just walking around the neighborhood. Nature is kind of like the parachute I attach myself to when I’m jumping out of a plane into scary territory. It feels like the beauty of it catches me when I’m getting deep into that morass and darkness.

As influential as geography is in your work, how has living outside of the South, in places like St. Louis and London, impacted your writing?

St. Louis doesn’t feel like the South to me; There’s a different way that Midwesterners relate to each other. I think the poems I’ve written here feel more like St. Louis. And, of course, this is a city, so they are a bit more concerned with urbanity. But I don’t think that the urban landscape is something that is outside of the realm of eco-poetry. I’ve also been returning lately to my time living in London.

While I was there, I got a degree in poetic practice at Royal Holloway, University of London. That program emphasizes structure and pushing the bounds of language rather than learning how to use written rules. This opened my mind to what I could use as an influence, and my collection includes a few ekphrastic poems. These are poems that engage with another work of art, object, or event. One example is my poem “Love Poem in a Black Field,” which starts with a photo caption.

There’s a prevailing notion in poetry that if a poem has an epigraph or something like that, it means the poem itself isn’t doing enough of the work. I don’t agree with that. My poems sometimes necessitate epigraphs because of all of the history they carry. I’d rather have too much information on the page than leave people in the dark and not allow them to fully appreciate the story. I’m more interested in preserving the story than in poetic integrity, whatever that means.

What has it been like to be in the WashU MFA program?

I’ve gotten so much out of it. Carl Phillips is a major influence for me, so the opportunity to study with him is one of the reasons I came here. Being in both his and Mary Jo Bang’s workshops have challenged me. We are required to produce a poem every couple of weeks, which forces you to experiment and try things on the page. It’s been really rewarding.

What advice do you have for other young poets?

It feels very fortuitous to be in the position where I’m having my book come out in the second year of my MFA program. But it’s not something I would advise people to rush into. The work came out of an impulse, something I was passionate about. For people interested in following this path, I’d say write until you get to that level of passion. Only then should you start thinking about books and publishing. Getting into that too soon can diminish the art.

I want to make sure people prioritize protecting their art and their growth. Once you are ready, you won’t be able to stop. I don’t even remember writing a lot of this book. I just couldn’t turn the water off.

Hometown: Chesapeake, Virginia

Degrees: Bachelor’s in psychology from Spelman College, Master’s in poetic practice from Royal Holloway, University of London, MFA candidate in English at WashU

Honors: Furious Flower Prize, Cave Canem Poetry Prize, Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship

Next steps: Her first poetry collection, “Black Pastoral,” will be published in September.