Interview with Faculty Fellow Christina Ramos

A rebellious Indian proclaiming noble ancestry and entitlement; a military lieutenant foreshadowing the coming of revolution; a blasphemous, Creole embroiderer in possession of a notebook filled with pornographic content. These individuals all shared one thing in common. During the late 18th century, they were deemed to be mad and were forcefully admitted to the Hospital de San Hipólito in Mexico City, the first hospital of the Americas to specialize in the care and confinement of the mentally disturbed. In her current book-in-progress, “Bedlam in the New World,” Faculty Fellow and historian of medicine Christina Ramos reconstructs the hospital’s history, as well as the lives of some of its most notorious patients who fell afoul of the Inquisition and secular criminal courts, to write a new history of madness during the Age of Enlightenment. Read on for a preview of her project.

During what years did the Hospital de San Hipólito operate and how did its mission change over time?

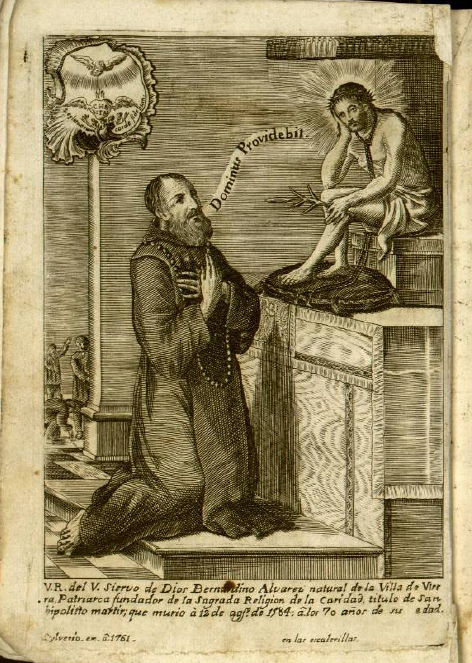

San Hipólito underwent many iterations throughout its expansive lifespan. Although early psychiatrists began to infiltrate the institution in the late 19th century, for much of its existence it was not an “asylum” in the psychiatric sense. Administered by a religious order, the Order of San Hipólito, it was foremost a charitable establishment that combined religious and medical models of care.

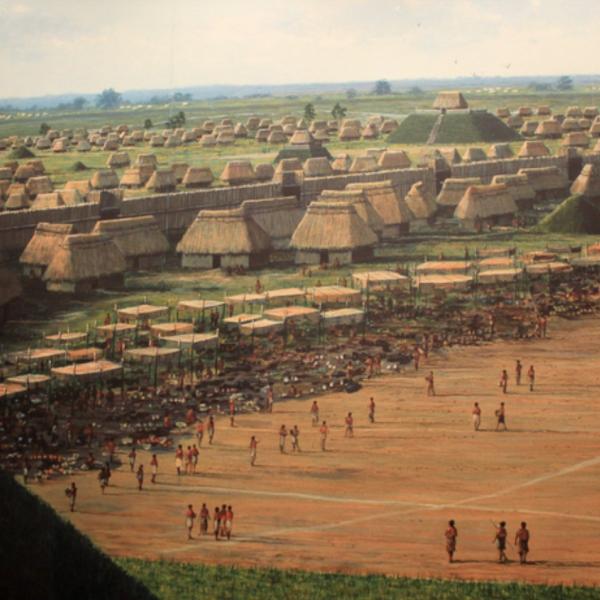

Legend has it that the hospital was founded in 1567 by repentant conquistador who was stirred to compassion by the pitiful plight of the sick and poor. It originally surfaced as a convalescent hospital that admitted a multiracial group of unfortunates labeled pobres dementes (mad paupers) and gradually came to concentrate on this marginal group exclusively.

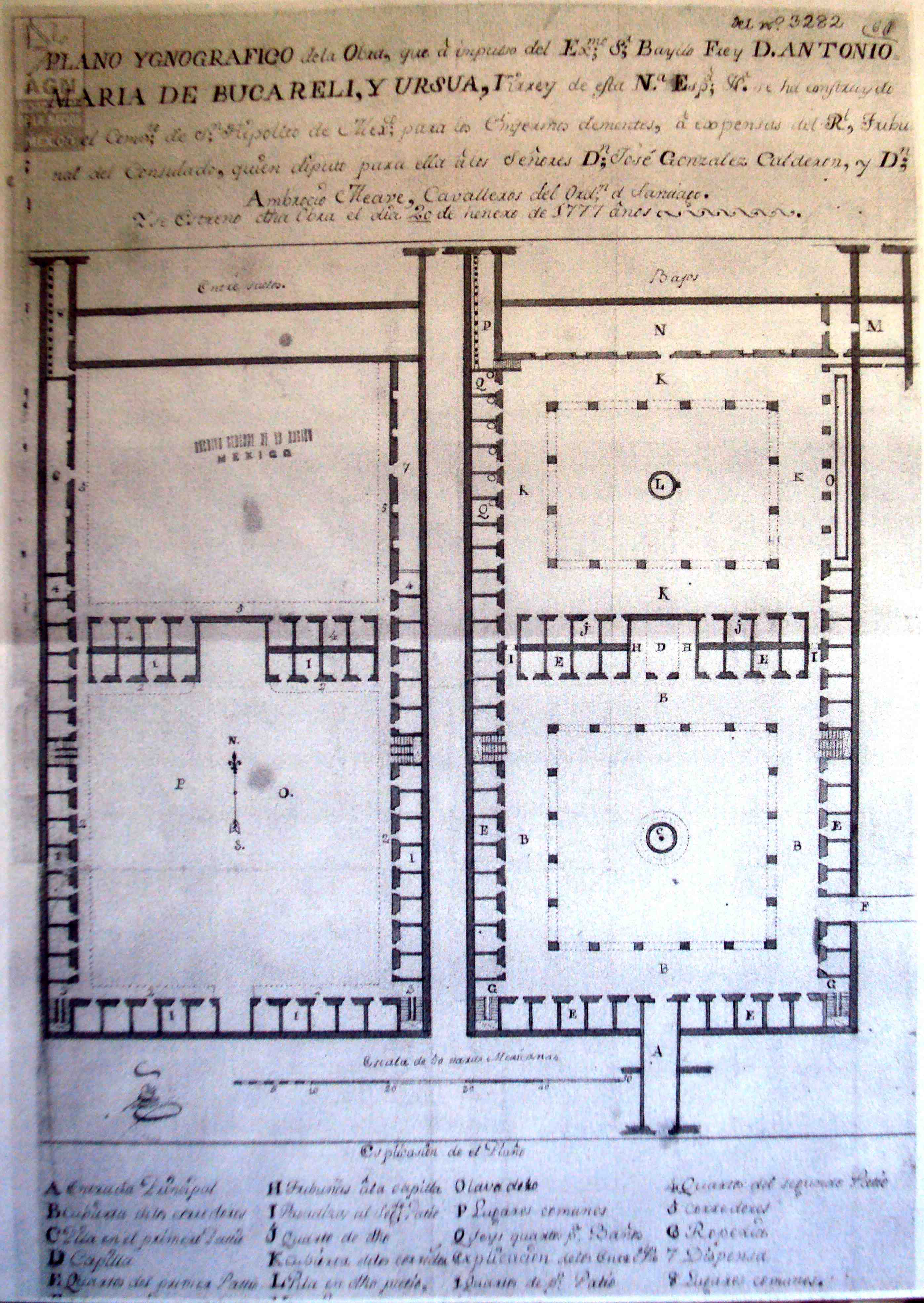

During the late 18th century, the focal point of the book, the hospital underwent significant transformations. Its once modest facilities were modernized and amplified to accommodate a swelling patient population, while its charitable mission to care for pobres dementes was touted in terms of a utilitarian service to the state and wider public. I argue that the hospital became a microcosm and colonial “laboratory” of the Hispanic Enlightenment, as the ideals of order, utility, rationalism and the public good came to shape new ideas of madness and its medical and institutional management, often in unexpected ways.

What were some of the reasons people were confined at San Hipólito? Who had the authority to send them there and why?

San Hipólito’s occupants were confined for myriad reasons. Most arrived because they were poor and lacked family and resources to provide for them. However, by the late 18th century, the hospital came to house a growing population who were not pobres dementes in the traditional sense: among them were allegedly insane criminals transferred from the Inquisition and secular criminal courts for crimes ranging from murder to blasphemy.

While traditional narratives have framed confinement as a process concerned more with social disciplining than therapy, my book argues against this, demonstrating that the hospital’s spaces enacted and refracted a complex history of medicalization occurring both within and without its walls. Colonial magistrates sent suspects to San Hipólito because they began to insist that madness was a disease with an underlying physiological basis, even though the process of determining who was mad and who was feigning was necessarily messy and contested, with confinement often emerging as an ad hoc, makeshift arrangement.

Is there a case of a particular San Hipólito patient that stands out to you?

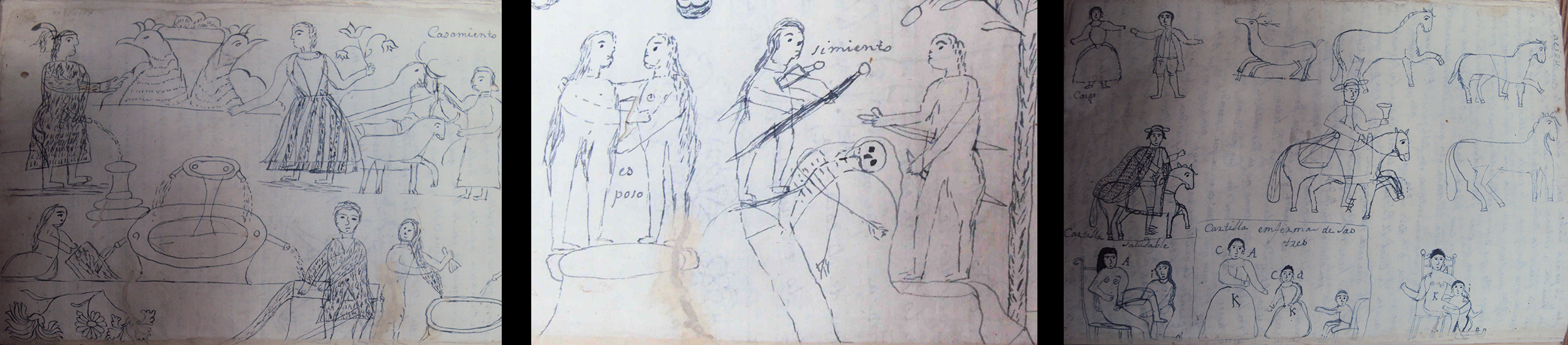

The cases are utterly engrossing and one of the main reasons I undertook the project. For its visual evidence, the trial against José Ventura Gonzalez, a native of Toluca who was known throughout his community as “Tebanillo,” particularly stands out. In 1789, Tebanillo was denounced to the Inquisition for irreverent claims, eventually making his way to San Hipólito after inquisitors determined him to be mad. An embroider by occupation, he kept a notebook in which he would draw embroidery designs and related sketches, which the inquisitors uncovered during their investigation and filed as evidence. While some of the images were innocuous illustrations of flowers clearly intended for stitching, others were of a crude variety with pornographic overtones.

Inquisitors not only kept records of madness; they also shaped the way madness was manifested and archived. I argue that the images reproduced in material form some of the epistemological dilemmas inquisitors encountered when making judgments about flawed mental states. Were Tebanillo’s sketches a testament to his troubled and disordered mind? Or did they simply expose in material form his perverted and morally debase character and conscience? The Inquisition, after all, was in the business of interrogating inward states of reasoning and conscience; because of this, its agents often unwittingly found themselves at the forefront in devising new modes for understanding the complexities of human reasoning and the nuances of intent. By the late 18th century, their concerns could not be answered on the basis of lay testimony alone and required “proof” in the form of medical expertise.

You’re breaking new ground with this book project. Tell us how this research will fill in gaps in both the history of medicine and scholarship on the Enlightenment.

The project aims to decenter traditional histories of both madness and Enlightenment that have privileged Europe as the epicenter of the medical and intellectual developments that inform the modern world. The history of psychiatry’s “birth,” in particular, has often been told as geographically seated in Europe, France and England especially, with certain medical men elevated as pioneers of a new science with either liberating or deleterious consequences. The case of San Hipólito undoes this narrative, illustrating, among other things, the centrality of religious personnel, including inquisitors, in propelling madness’s medicalization long before the rise of psychiatry as a hegemonic science.

Headline image: “The Madhouse” by Francisco de Goya, 1812–19.