A popular Ampersand program is preparing the physicians of the future to understand the scientific and social aspects of cancer.

As a PreHealth biology major, Mishka Narasimhan knows the finer details of cancer down to the molecule. Her familiarity with DNA, oncogenes, cancer cells, and antibodies will serve her well as she works to become an oncologist, but she’ll have to call on deeper, more personal insights to become a truly successful physician. Thanks to Hallmarks of Cancer and Patient Care — a two-year Ampersand program that explores the disease at every level — she feels up to the challenge.

As part of the program’s inaugural cohort, Narasimhan spent the spring semester of 2022 getting to know a group of cancer survivors. Over Zoom, the students and survivors discussed their days, shared worries and accomplishments, and, in a highlight for all, made art.

Anthony Smith, biology lecturer and coordinator of undergraduate research experiences, and Dinesh Thotala, now an associate professor of radiation oncology and director of cancer biology at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, introduced Hallmarks of Cancer and Patient Care in 2020 to fill a pressing need. Over a third of all Arts & Sciences undergraduates have their sights on a career in the health field, said Smith, who was himself a PreHealth biology major at WashU before earning a doctorate in microbiology and immunology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Smith went on to discover a love for teaching as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota Medical School and returned to WashU as an assistant dean in Arts & Sciences.

Whether new undergrads aspire to geriatrics, pediatrics, or any health field in between, an understanding of cancer will be a part of the job. “If students are eventually going into healthcare, they’re going to interact with cancer at some point along their journey,” Smith said. “We wanted to help them develop the skills to be successful.” Hallmarks adds to Arts & Sciences’ growing array of offerings for students interested in medicine, including a multi-semester MedPrep program and anthropology courses on global health and the environment.

For the initial cohort, Smith and Thotala received piles of applications and personal essays from hopeful students, far outpacing the number of available slots. They narrowed the pool of applicants down to those who ticked every box: academic rigor, intellectual curiosity, and a desire to learn about every aspect of cancer. From that group, the final 20 students were selected.

While Smith and Thotala were surprised by the initial interest, it became clear that the program’s mission resonated with students. As part of their applications, many students wrote about their own experiences with cancer, including the loss of friends and relatives. “There is clearly a deep emotional connection to this program and this topic,” Smith said.

Like other Ampersand programs, Hallmarks gives first-year students a chance to dive into a particular topic in a small-group setting. The first two semesters cover the biology of cancer, including the mutations in healthy cells, the growth of tumors, and the underlying theories behind chemotherapy, radiation, and other treatments. In the third semester, students learn about the scientific method and the latest research on therapy, diagnosis, and other cutting-edge topics. In the fourth semester, Smith calls on a group of experts from Siteman Cancer Center and beyond to give students a fuller picture of the cancer community. “We have a lot of field trips and guest speakers, and it really opens the eyes of the students,” he said. “It’s not just about medical doctors. It’s nurses, social workers, dietitians, psychologists, and clergy. They can all make a meaningful difference to someone facing cancer.”

Students also have the chance to learn directly from survivors. From the outset, Smith wanted to inspire meaningful interactions between students and people who have personal experience with the disease. To reach that goal, he enlisted the help of Sarah Colby, coordinator of the Arts + Healthcare program at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, part of the WashU Medical Center.

Colby, a trained artist, is a fixture at the hospital, where she wheels a cart of paint, yarn, and other supplies from room to room, giving patients a break from their troubles and an outlet for creativity. “I see people at the hospital with all kinds of conditions, but there’s still something especially troubling about cancer. When you hear that word, your mind goes to the worst-case scenario. Art can be very helpful for those patients as a form of expression and diversion.”

To bring that approach to the Ampersand program, Colby worked closely with Rochelle Hobson, a hospice and oncology nurse who manages the Siteman Cancer Center’s Survivorship Program. Hobson reached out to her network to find a group of survivors who were interested in helping to train the next generation of physicians.

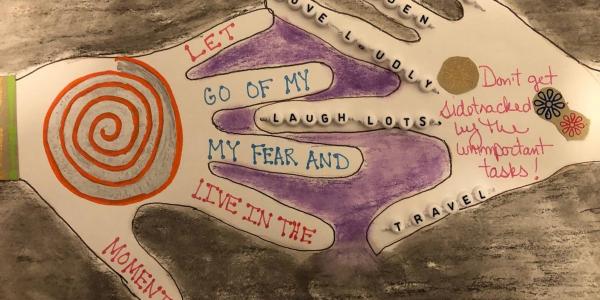

With Smith’s encouragement, Colby and Hobson built an art therapy support group that brought students and survivors together over paint, gel pens, and poetry. “The smallest interaction with someone can be incredibly important,” Colby said. “That’s a huge lesson for the students going forward if they want to be physicians.”

Not every student was an expert with a paintbrush, but they all brought a lot of energy and talent to the project, Colby said. “A lot of them are super creative. I’m so impressed, and I have so much hope for physicians of the future.”

I’m so impressed by the students in this program, and I have so much hope for physicians of the future.

The first round of Hallmarks took place during the pandemic, so face-to-face meetings between students and survivors weren’t possible. So, they turned to Zoom. Over the course of eight weeks, survivors converted their homes into miniature art studios using supplies Colby sent in the mail. In 90-minute sessions, the survivors and the students would craft mandalas, watercolors, and collages of family photos. “It felt like the survivors were in the room with us,” Narasimhan said. “We could all be vulnerable together.”

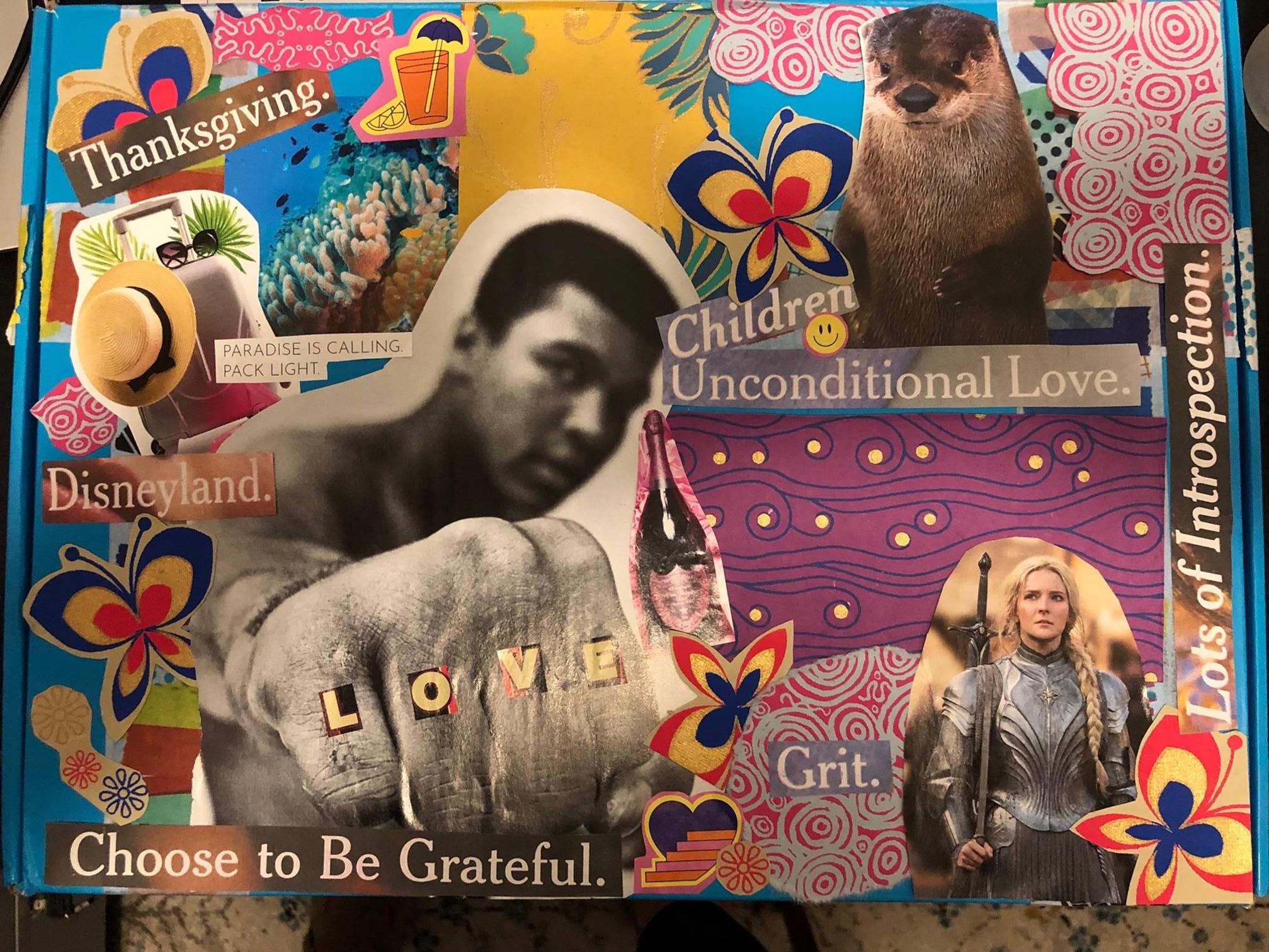

The images from the survivors spoke volumes. In her first session, Kathleen Stomps, who had just started chemotherapy for endometrial cancer, drew a dark, moody picture of an IV bag with the words “time passes with measured, poisonous drips.” Later, she decorated her box of art supplies with a collage of butterflies, Muhammad Ali, and the phrase “choose to be grateful.”

Stomps volunteered for the program partly because she wanted a respite from the routine of cancer treatment and the isolation of the pandemic. She was immediately struck by the students’ compassion and enthusiasm. “These students are really committed to becoming the best physicians possible,” said Stomps, who is now cancer free. “It was a short-term interaction, but it just blew me away.”

The art gave everyone a common purpose, but it also sparked conversations. Many of those discussions drifted toward everyday life. The students would talk about spring break plans or studying for finals; the survivors would talk about grandkids, hobbies, and fears. “It was beautiful and powerful,” Smith said.

The art therapy sessions played to the strengths of McKenzie Halpert, now a senior majoring in biology and minoring in psychological and brain sciences. “I was able to share my passion for art and connect with people using that form of self-expression,” said Halpert, whose grandmother died of breast cancer a few months before the program launched in 2020. She recalls a powerful image from one survivor: a watercolor of a butterfly emerging in front of a sunrise. “It represented the feeling of optimism and how she’s looking forward,” Halpert said. “She had so much positive energy that she was putting out there and into her work.”

Halpert was so inspired by her time in the Ampersand program that, after she completed it, she began volunteering in the oncology unit at the Barnes-Jewish Center for Advanced Medicine. After graduation, she plans on going to medical school to become a physician.

Elina Deshpande is one of the students just starting their second year of the program. The sophomore feels deeply connected to the 19 other students in her cohort. The shared classes have created a bond that rarely happens in large lecture halls, she said.

Before she arrived at WashU, Deshpande saw herself eventually practicing general medicine, perhaps as a pediatrician or family doctor. “But after starting the program, I’ve had a shift,” she said. “I’m really fascinated by cancer and cancer biology. New things are always being presented, new questions are being asked, and new answers are being provided. So, now I’m thinking about becoming a cancer specialist, maybe a pediatric oncologist.”

Deshpande is looking forward to meeting and working with survivors in the spring. While she doesn’t have much skill with a paintbrush or pencil — her preferred artistic medium is dance — she anticipates that those interactions will give her a chance to understand how patients feel about their disease, their lives, and their treatment. “I’m minoring in Jewish, Islamic, and Middle Eastern studies, and I really want to see how culture and religion influences the ways people look at medicine,” she said.

Now a senior, Narasimhan looks back fondly on her time in Hallmarks, an experience she strongly recommends to incoming WashU students. “Anyone who is interested in becoming a doctor should apply for this program,” she said. “Humanity is so central to the practice of medicine.”