Devin Naar, AB ’05, will explore the history of Ottoman Jews in a virtual seminar this Sunday, April 18.

As an undergraduate studying history at Washington University in St. Louis, Devin Naar first began to make sense of the complex cultural roots of his own family. How could it be that his grandparents’ generation, born in present-day Greece, spoke a Spanish-based language that they wrote in Hebrew letters? Naar’s grandparents were Sephardic Jews, part of a group whose ancestors had been exiled from Spain in 1492 and found refuge across the Mediterranean, where they established thriving communities in the Ottoman Empire. Their language, today highly endangered, is known as Ladino.

Over the course of the next 15 years, a fascination with Ladino and its speakers led Naar on a remarkable journey across the globe, as he tracked down stolen archives, learned multiple languages, and became one of only a handful of people in the United States to decipher a Ladino cursive script – all in an effort to revive the previously lost history of Ottoman Jews. Today, Naar is the Isaac Alhadeff Professor of Sephardic Studies and the founder and chair of the Sephardic Studies Program at the University of Washington. In this position, he has established the largest digital collection in the country of texts in Ladino.

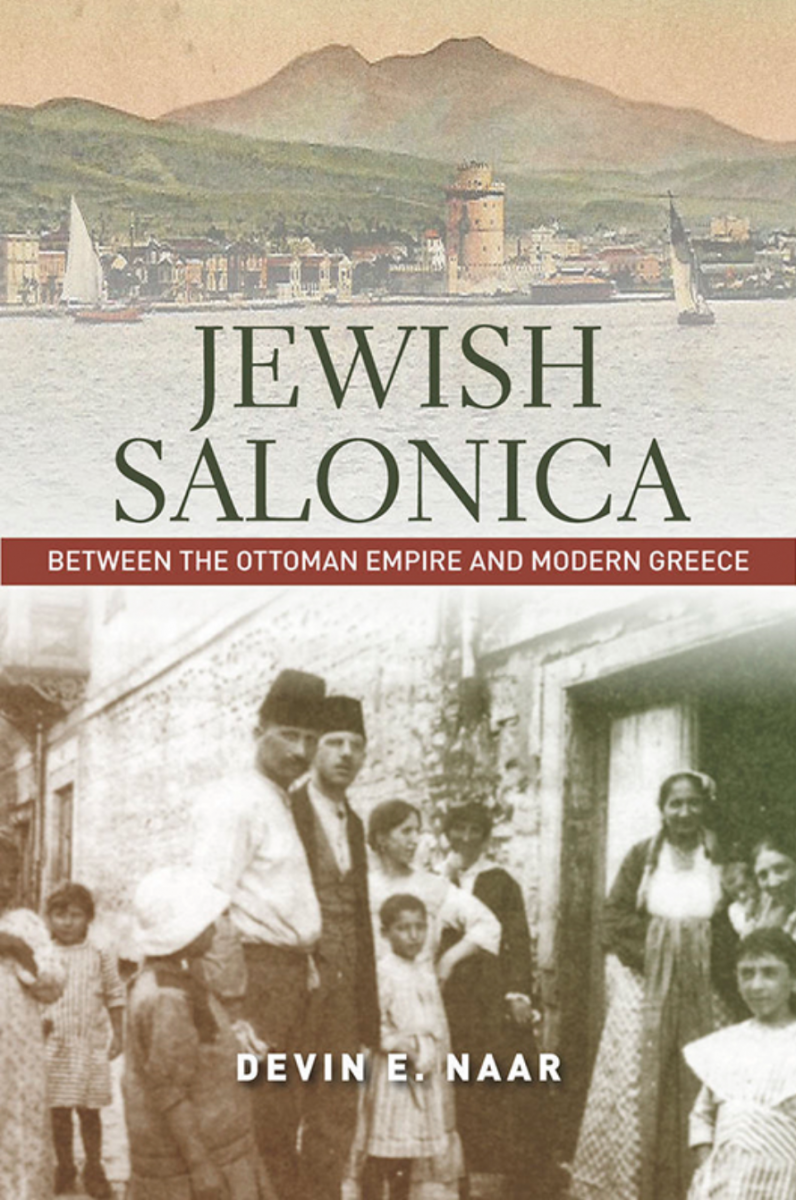

When creating the archive and writing his book, Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece, Naar faced a major challenge. During World War II, Nazis had rounded up and deported the Jews in the city of Salonica (Thessaloniki), the second biggest city in Greece and once home to the largest Ladino-speaking Sephardic community in the world.

“The Nazis had confiscated the archives and libraries of the Jewish community of Salonica during the war. It was largely believed that much had been destroyed and that what survived was locked away in the former Soviet Secret Military archive in Moscow,” Naar explained.

To bring this lost history to light, Naar took on research methods resembling those of Indiana Jones, embarking on a global hunt for more hidden archives. “I discovered that various segments had survived the war and afterwards wound up in different places – not only in Moscow, but in Jewish archives in New York and Jerusalem,” he said.

Following his graduation from WashU, Naar spent a year in Greece as a Fulbright scholar, where he found a cache of archives in an old storage facility. Naar shared, “It was a historian’s dream: vast amounts of previously unstudied archival material. But it was also a bit of a nightmare because the material was initially in such disarray.”

Finding these archives was only one part of the research process. To understand the writing, Naar has learned Hebrew, French, Greek, and most importantly, Ladino.

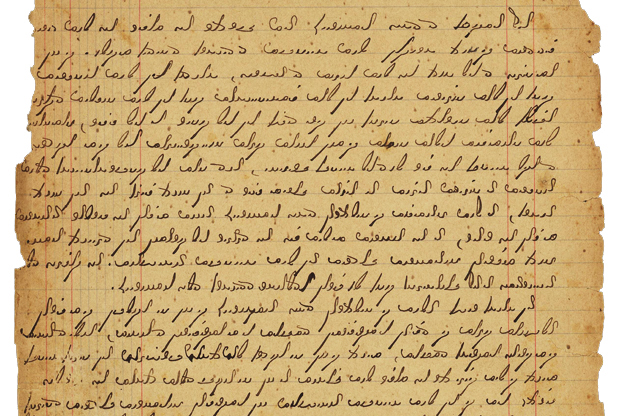

Letters Naar collected from his family as an undergraduate were written in Ladino in an unrecognizable script, which he had to decipher. “There were few resources available and fell beyond the expertise of faculty,” Naar recounted. “I eventually found a chart in an old book that indicated which squiggly marks corresponded to which “standard” Hebrew letters. And I began to decode the letters."

Through this record, Naar discovered a tragic chapter of his family history. On the eve of World War II, Nazis deported Naar’s great uncle and his family to their deaths at Auschwitz Birkenau in 1943. Their story mirrored the fate of nearly all of Salonica’s 50,000 Jews.

Understanding these letters became a crucial first step enabling Naar to rediscover Ottoman Jewish history in earnest. “Suddenly, I had become among one of the few people in the U.S. who could read and decipher texts in this now defunct Sephardic Hebrew cursive, known as solitreo,” Naar said. “So I couldn’t stop there as a whole new, largely occluded world began to open up.”

“I eventually found a chart in an old book that indicated which squiggly marks corresponded to which “standard” Hebrew letters ... I couldn’t stop there as a whole new, largely occluded world began to open up.”

Naar credits his pioneering work to the professors and students he worked with as an undergraduate at Washington University. His suitemate Brian Berman helped him scan his family’s letters and develop www.solitreo.com, a website anyone can use to decode or compose writing in several Ladino alphabets. Roz Kohen Drohobycer, herself a native Ladino-speaker from Istanbul and then a librarian at WashU, connected him with other scholars and activists across the world working on Ladino.

“Among the many faculty who nurtured my interests,” Naar added, “Hillel Kieval, a professor of history and in JIMES, was really instrumental in supporting and encouraging my research. He supervised my senior thesis (which won the award for best thesis in Jewish studies) and encouraged me to go to graduate school, even get a PhD and write a dissertation about Sephardic history. I remember thinking that that sounded like a crazy idea! I am glad I pursued that path!”

Naar hopes his work helps open up a more diverse and nuanced understanding of Jewish history. “There is a kind of imbalance in the way that we talk about and study history in general — it tends to be Eurocentric,” Naar explained. "That same approach has tended to shape how we understand Jewish history, especially in the United States.” This formed a concrete obstacle personally and professionally at the beginning of Naar’s academic journey.

“When I was writing my WashU thesis,” Naar recalled, “while there had been hundreds of books published about American Jewish history by academics, there was not even one book about Sephardic Jews from the former Ottoman Empire in the U.S. – since then only one such book has been published. It was like my family’s experience did not exist. So in my undergraduate thesis, and in my research and teaching ever since, I have been interested in trying to reframe both scholarly and public discussions about Jewish history, to push back against the dominant Eurocentric focus, or Ashkenazi-center focus in the Jewish context, and then to see how the narrative as a whole ought to shift.”

Lastly, Naar hopes to shine a light on ethnic discrimination. He explained, “W.E.B. Dubois famously wrote that the 'color line' served as the defining problem of the 20th century. When Ottoman Jews arrived in the United States they encountered the color line in a profound way—as Jews speaking essentially Spanish and coming from the Muslim world.” The federal government, prospective employers, and even Jewish community leaders inconsistently deemed the newcomers white or non-white and at different times mistook them to be Muslims, Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Italians, Mexicans, or Puerto Ricans – groups who have all faced their own unique stereotyping and disparate treatment in this country.

“Exploring the history of the United States through the prism of Sephardic Jews reveals the instability of racial and ethnic categories, and at the same time, the power of the color line to include and exclude individuals and communities from a wide array of rights and privileges,” Naar explained.

On Sunday, April 18, Naar will return virtually to St. Louis to deliver a lecture titled “From the Mediterranean to St. Louis and Beyond: Sephardic Jews, Migration, and Race in the United States.” This lecture will tell the little-known story of Ottoman Jews in the United States, including their struggles with the American immigration system, as well as their initial forays into establishing new communities, institutions, and cultural initiatives across the country —including in St. Louis.

“St. Louis frames my talk,” Naar shared. Notable figures he has researched include Nessim Hanoka, who in 1915 may have become the first Ottoman Jew to graduate from an American university, and Michael Castro, St. Louis’ first Poet Laureate. Like Naar, both were Washington University alumni.

To hear Naar's upcoming talk, view event details or register for the event.