Making Transdisciplinarity Work convened academics, funders, and administrators to discuss how breaking down departmental barriers can create more powerful scholarship.

Why don’t radiologists and chemists collaborate more frequently?

The question began nagging at Department of Chemistry graduate student Collin Merrick when he attended a talk from a Washington University radiology professor in 2022. It came up again and again in the presentation and the discussions that followed – what was keeping two disciplines that naturally complemented one another apart?

“There were only a handful of graduate students and faculty in attendance,” Merrick said. “My main takeaway from this radiologist was ‘we need chemists,’ but chemists wouldn’t even show up to hear this cry for help. It was obvious that we should work together, but we just don’t.”

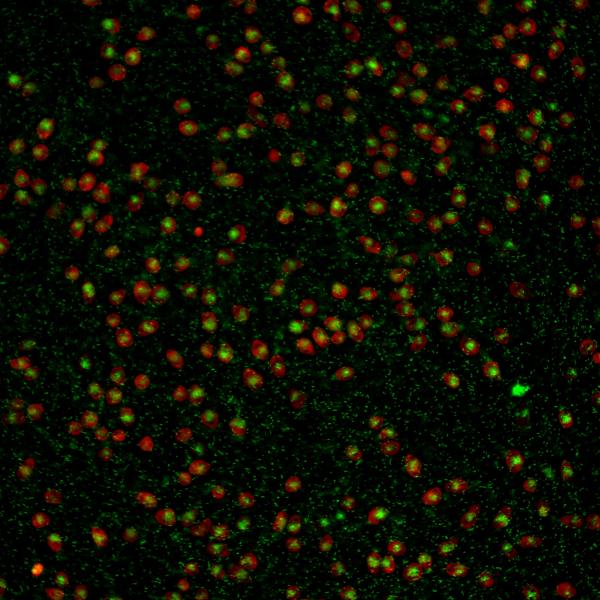

Instead of leaving the problem unresolved, Merrick continued the conversation with a group of like-minded faculty members. Their shared commitment to bridging that gap eventually birthed Next Frontiers in Radio Chemistry, a multi-year project supported by the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures (ITF), a signature initiative of the Arts & Sciences Strategic Plan. Uniting a transdisciplinary team of scientists, including chemists, radiologists, and more, the team works to advance infectious disease imaging.

That journey – identifying a potential collaboration across disciplines and then breaking down the academic barriers to make it a reality – was the focus of Making Transdisciplinarity Work, a February mini-conference hosted by ITF. Featuring ITF-funded groups, representatives from funding organizations, and academic leaders, the conference aimed to identify success stories and best practices for transdisciplinary scholarship and collaborations.

In his keynote presentation for the conference, Ed Balleisen, vice provost of interdisciplinary studies at Duke University, laid out the promises and pitfalls of this style of collaboration. On the plus side, research teams armed with transdisciplinary expertise are uniquely situated to address the most pressing issues of our time, and can give themselves the inside track to secure external funding through their unique combinations of perspectives.

But the degree of difficulty is high: team members must adapt to each other’s diverse scholarly languages, research styles, and cultural expectations, all while meeting rigorous research standards and deadlines.

Those pluses and minuses have played out through ITF’s work at Washington University.

As a signature initiative within the Arts & Sciences Strategic Plan, made possible by the vision of Dean Feng Sheng Hu, Provost Beverly Wendland, and Vice Provost Mary McKay, the Incubator has generated some significant wins. At its onset in late 2022, the Incubator funded nine multi-year transdisciplinary projects, along with five teams working on one-year grants. This academic year alone, three of those groups – The Human-Wildlife Interface, Police Body Camera Metadata, and The St. Louis Policy Initiative – have secured significant external funding to expand the scope of their work, a clear sign that transdisciplinary scholarship can make a major impact.

Beyond external funding secured, teams have supercharged collaborative culture across the university, helped to create new courses, host symposia, and bring community-building events to campus.

But even a successful group like Next Frontiers in Radio Chemistry illustrates that transdisciplinary teams must invest significant time and effort to build a thriving team culture. As Merrick and Next Frontiers faculty co-lead Timothy Wencewicz noted, there are a variety of cultural and practical barriers that prevent scientists in different WashU departments from collaborating. Not the least of which: some team members work on the Danforth Campus, while others are on the Medical Campus.

“The only way to overcome that is to go over to someone else’s lab – to see how radiology functions,” said Wencewicz, an associate professor of chemistry. “You want to bring the chemistry perspective, but just being willing to go over there in the first place has been a big factor. You have to put forth, ‘what can I contribute?’ and not, ‘what can I get out of it?’”

Anna Harvey, president of the Social Science Research Council, echoed that sentiment as part of a panel discussion featuring representatives from regional and national foundations.

“Do you care about solving the problem, or do you just want to get an article in a journal?” Harvey said. “Our single largest predictor of success for this kind of work is having an implementation partner. In attracting funding to our work, we look for teams who take seriously the idea of actually solving the problem, not just writing about the problem.”

Learn more about the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures and the projects it supports here.