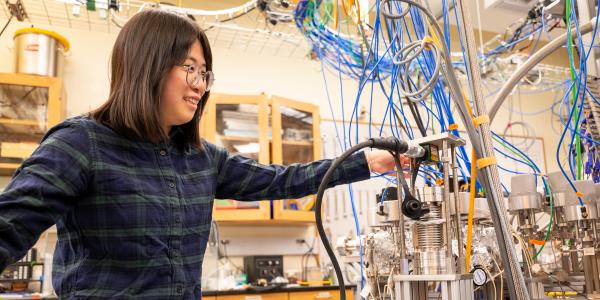

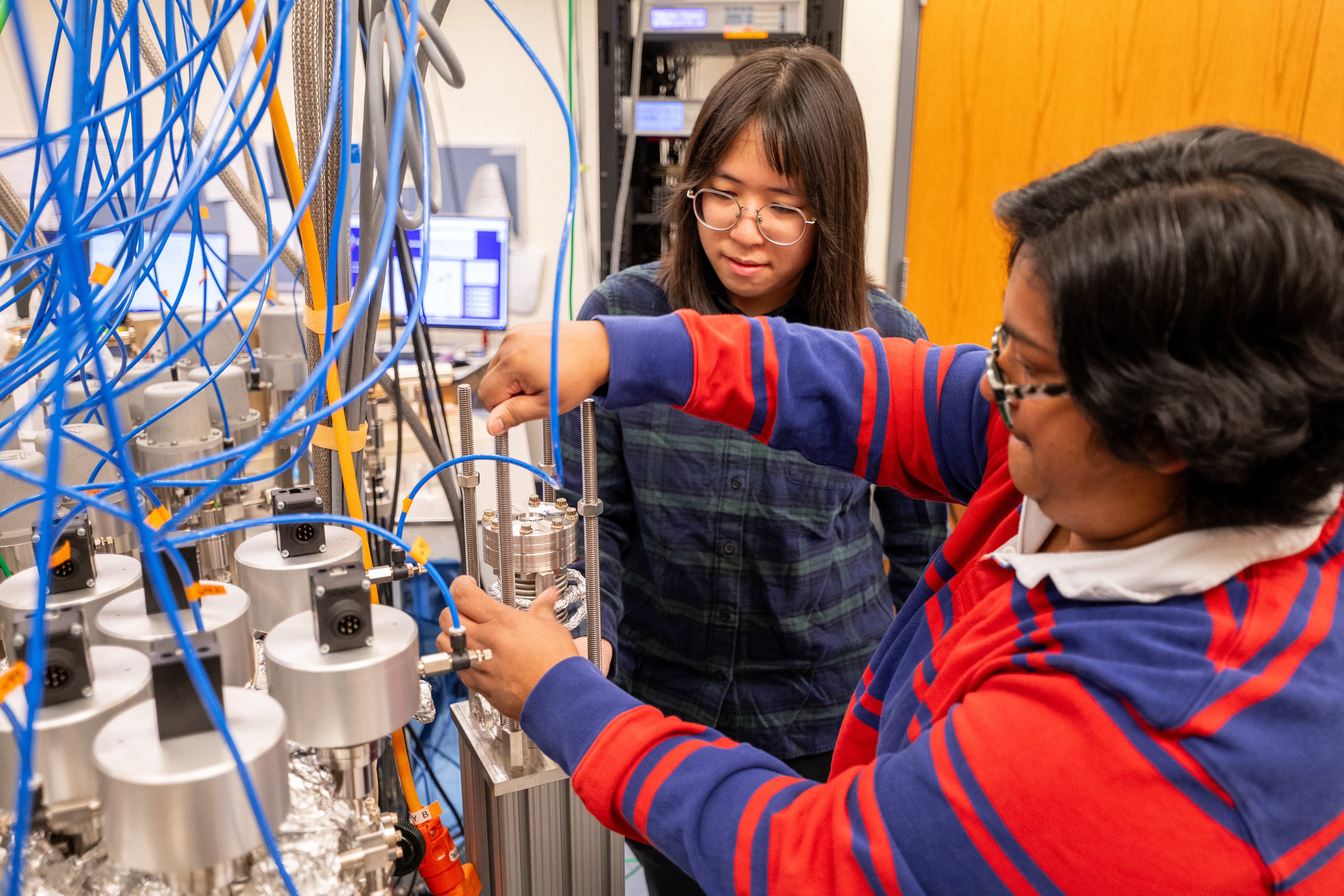

Assistant Professor Rita Parai and graduate student Judy Zhang got a glimpse of Earth’s history by tracking infinitesimal levels of noble gases in volcanic rocks.

In Earth science, small details can help explain massive events. Rita Parai, assistant professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences, uses precision equipment to measure trace levels of noble gases in rocks, samples that can provide key insights into planetary evolution.

In a study published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Parai and graduate student Judy Zhang used measurements of noble gases from volcanic rocks from the Cook and Austral islands to show that plate tectonics have been delivering gases from the surface into deep Earth for more than 2.5 billion years. John Lassiter of the University of Texas at Austin was a co-author of the study.

Noble gases are especially helpful for deep-time investigations because they are chemically inert. Some of their isotopes were trapped in the interior 4.5 billion years ago when the Earth first formed, Zhang said. “They leave a lasting imprint on the rocks.”

In Parai’s laboratory, Zhang was able to measure multiple noble gas elements and their isotopes, including the rare element xenon. The pattern of noble gas abundances and their distinctive isotopic signatures told an important story, Zhang said.

As Zhang explained, the Cook-Austral Island rocks were delivered from deep in the planet’s mantle to the Earth's surface through volcanic eruptions. The signature noble gases in the rocks showed that deep in the past, tectonic plates were relatively cool when they underwent subduction — the process where surface rock sinks to the mantle — some 2.5 billion years ago.

Some researchers theorized that, back then, the planet might have been much hotter and much harsher than the world we know today. The presence of xenon shows subduction happened under geological conditions similar to modern times. “If the rock had been subducted at much higher temperatures, it would have lost all of its gases,” Zhang said. “This is a very exciting finding.”

Detecting atoms of xenon isn’t like finding a needle in a haystack; it’s like finding a microscopic needle in an entire hayfield. Noble gases are already a rare feature in rock, and xenon that can trace ancient plate tectonics is exponentially more elusive. “There are only about 100,000 xenon atoms for every gram of material,” Parai said. That's about 1 out of every 10 quadrillion atoms.

The researchers had to extract gas from large amounts of the mineral olivine in these rocks to get the faintest signal. “It’s like we’re figuring out how to squeeze blood from a stone,” Parai said.

Last December, Zhang collected more rock samples from the ocean floor during a 28-day research cruise in the South Pacific led by Doug Wiens, the Robert S. Brookings Distinguished Professor. Analysis of the rocks in Parai’s lab should offer even more insights into the Earth’s deep past. “We’re pushing the boundaries of analysis to look back billions of years,” Zhang said.

(Header image by Sean Garcia.)