The award-winning writer discusses his journey to poetry, his creative process, and his decision to join WashU’s English department this fall.

Award-winning poet Eduardo C. Corral will soon join the Department of English as a member of the MFA faculty.

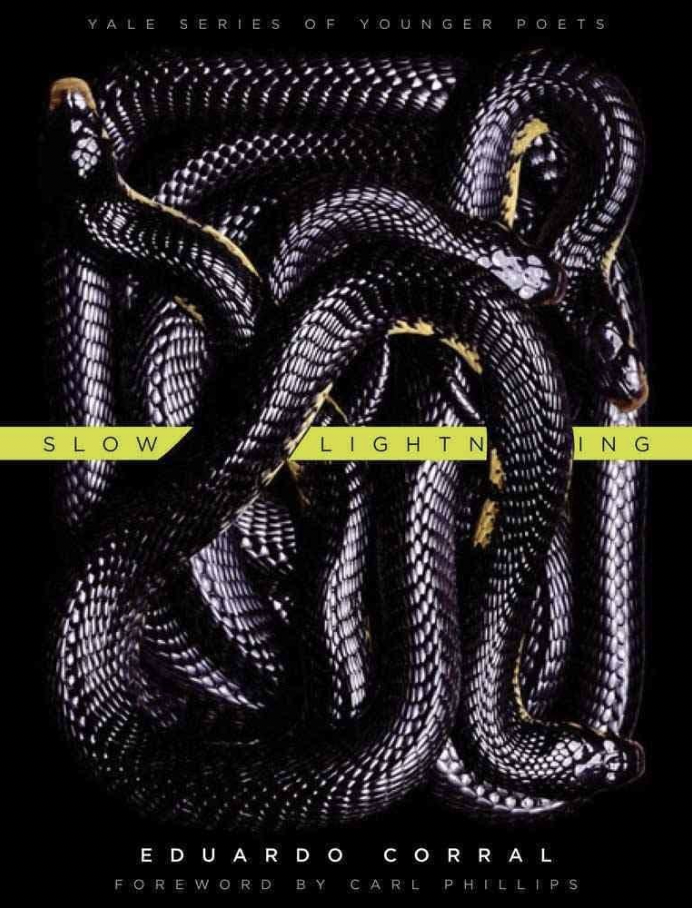

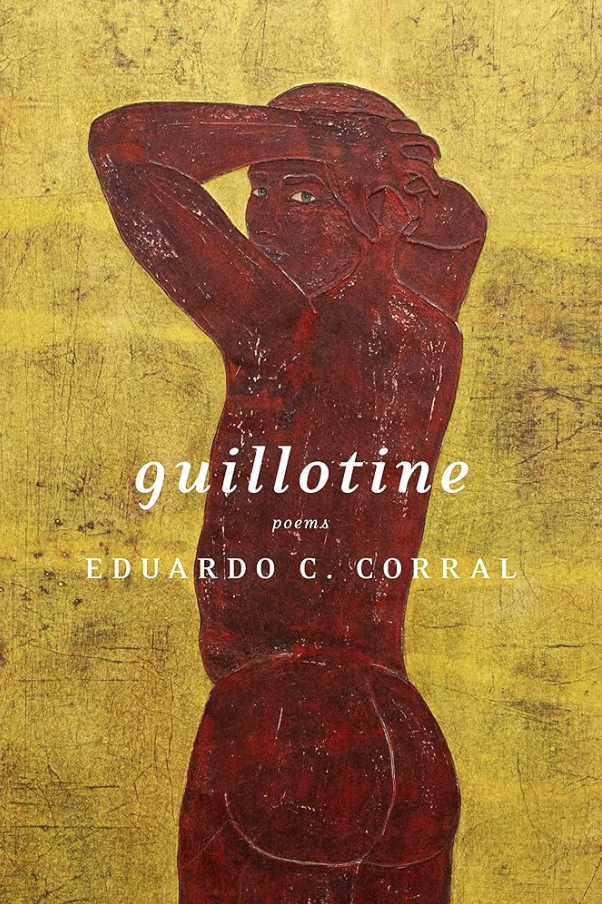

His first poetry collection, “Slow Lightning,” was selected by Carl Phillips, professor of English, for the 2011 Yale Series of Younger Poets prize, and his second manuscript, “Guillotine,” was longlisted for the National Book Award. Corral currently teaches poetry in the MFA program at North Carolina State University.

To celebrate National Poetry Month, Corral sat down with the Ampersand to talk about poetry, his creative process, and his decision to join the WashU English department.

How did you become a poet?

I’m from a small town in southern Arizona and grew up in a Spanish-speaking home. Even as a child, I saw how language was malleable and shaped by the environment. I got my bachelor’s in Chicano (Mexican-American) studies at Arizona State University and that’s where I became a poet.

I had signed up for a Chicano-lit course at ASU but, after I saw on the syllabus that there was a poetry workshop, I walked to the registrar’s office to drop the class. But then I thought, if I dropped it, I might have to take an early morning class, so I stayed. I turned in my first poem and my teacher, Dr. Arturo Aldama, saw something in me. He told me to turn in another one the next week. That semester, he was my audience of one.

In high school, I’d only read Whitman and Dickenson — both long dead — but Dr. Aldama introduced me to Derek Walcott, Rita Tao, Gary Soto, and Phillip Levine. They ignited my passion. I remember reading a line from Walcott — “Wind stretches its blanket over our heads” — and having a visceral reaction. From that moment on, I took poetry seriously.

I shifted my ASU classes to creative writing. The faculty there were so kind to me, especially Norman Dubie. He was rigorous with my work but also nourishing. Rigor and nourishment. These two words describe my approach to teaching.

Did you start your career as a poet after graduating from ASU?

Well, no. First I went to get a master’s degree at the Iowa Writers Workshop. That was a difficult time for me. Though I’m still in touch with some of my cohort, and I must give credit to some professors who gave me wonderful advice, it was not the right program for me. I was writing poems to impress my classmates and professors instead of listening to the language. I left that program with my gifts diminished.

After I graduated from Iowa, I returned to Arizona and lived with my parents. I worked at Home Depot, which was a job I could leave behind at the end of the day. At home, I could focus on language and my manuscript. I’m very slow and deliberate, and it took me about nine and a half years for my book “Slow Lightning” to come out. In 2011, I was awarded the Yale Series of Younger Poets prize. Carl Phillips was the one who told me I’d won, and that phone call changed my life. I never worked at Home Depot again.

In 2012, I won the Whiting Award for “Slow Lightning” and that allowed me to move to New York City. I also started teaching at Drew University and in the Columbia University MFA program. It was a wonderful period for me personally and professionally.

You are known for using Spanish and English in tandem in some of your poems. What’s behind that choice?

In Iowa, there were no Spanish speakers in my cohort. But back in Arizona, it just dawned on me one day that sometimes my thoughts would begin in English and end in Spanish. It popped into my head: why can’t I write a poem like that? People thought this was new, but I’d seen it before in Chicano and Latinx literature from the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

I only incorporate Spanish when it comes organically in the drafting process. If I’m working on a poem and Spanish makes itself visible in a line or stanza, and if it survives my revision process, it was meant to be. I don’t like using Spanish as an ethnic embellishment or as a gesture to otherness. It has to be part of the musical structure and image field of that poem. Not all of my poems do that, but sometimes it feels necessary.

You’ve been recognized as a Latino poet and a queer poet. How do you feel about these designations of your identity?

Some writers have anxiety if there are modifiers before the word “poet,” but I’ve never felt that way. As Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jericho Brown put it, each modifier is another window or way of viewing the world. As a poet, language itself is a window — be it English or Spanish. Anything said before my name — Latinx, from the borderlands, queer, oldest child, college graduate — represents a window that allows me to see the world from different angles.

What’s your creative process like? How important do you think it is to have a set process?

Like many other artists and scientists, I move through the world with my five senses attuned. I never worry about not writing or producing regularly as long as my notebooks are filled daily or weekly with patterns, observations, and things I glean from the world. If I pause because I’m bewildered, confused, delighted, or something catches one of my senses, it goes into the notebook.

This is something I model with my students, too. I make them keep notebooks and, by the end of our time together, they have articulated to me and their classmates a writing practice that can sustain them in their post-MFA years. That time tends to be full of doubt and anxiety, and they will need to rely on their practice to carry them forward.

I floundered for years until I developed my own writing practice. Now, everything — my practices, my strategies, my revision, my reading, my pedagogical approach — is rooted in my writing practice. My teaching is shaped by my life as a practicing poet.

What do you hope to bring to the MFA faculty at WashU?

I’m very excited to start teaching at WashU. It will be a little bittersweet to leave my students and colleagues in North Carolina, but it seems like the right move at the right time. I’m well aware of the huge legacy of the MFA program at WashU; the graduates they produce are amazing. I want to add my own perspective. I hope to complicate and to enlarge what Carl Phillips and Mary Jo Bang have been doing.

(Header image: Pexels Pixabay)