High schoolers have many opportunities to work with Arts & Sciences faculty members, conduct research, and take college-level courses — experiences that often go on to kickstart careers.

Long before she graduated this year from Lindbergh High School, Althea Bartz was deeply immersed in WashU. She spent much of the summer of 2020 identifying native plants, catching bumblebees, and burning weeds in the Shaw Institute Field Training (SIFT) program. Inspired by her introduction to ecology research, she spent the next two summers as a student followed by one summer as an undergrad fellow in the Tyson Environmental Research Apprenticeship (TERA) program at Tyson Research Center, where, among other things, she used camera-trap photos to track the movements and behaviors of white-tailed deer.

Those hours in the field put Bartz on a new path. This fall, she started her first year in WashU’s environmental studies program, a step toward her goal of becoming an ecologist. “I didn’t really even know that ecology was a thing before I started at SIFT,” she said. “That program changed my life.”

At WashU, an Arts & Sciences education isn’t just for university students. High schoolers have many opportunities to work with faculty, conduct research, and take courses that go beyond the usual high school curriculum. Whether they’re tracking deer, studying the human brain, or workshopping a short story, they’re getting a college experience that could transform their futures.

Pre-College programs

Inspiring young people to pursue higher education is a core part of the WashU mission, said Becki Baker, director of Pre-College Programs in the College of Arts & Sciences. That mission is the driving force behind the programs that bring hundreds of high schoolers from across the country and around the world to WashU every summer. “Our programs really focus on the true WashU experience,” Baker said. “These students are being taught by the same instructors who teach our undergrads, and they're being mentored by our WashU undergrads and graduate students.”

Different Pre-College programs offer different levels of immersion. The Summer Scholars program — a five-week offering that has been a fixture of the Danforth Campus since 1984 — gives rising high school seniors a chance to sit side by side with WashU students, stay in residence halls and enroll in Arts & Sciences courses for credit. The classes are carefully curated to give students the best possible experience. “Most of the classes have 20 students or fewer,” Baker said. “Our team works closely with instructors to ensure students are finding success both inside and outside of the classroom.”

To make WashU even more accessible to a wider range of applicants, the university in 2011 also created shorter, more affordable non-credit options for high schoolers. Participants in the High School Summer Institutes program can craft poetry and fiction in the Creative Immersion Institute or take a deep-dive into ecological principals of sustainability as part of the Environmental Studies Institute. The Healthcare Continuum Institute — which looks at the collaborative roles of researchers, policy makers, and public health professionals to shape health care — is a popular option for students who hope to enter the field of medicine.

Roses Wong came to WashU in the summer of 2019 before her junior year of high school in Tucson, Arizona. Her visit was made possible by the Student Expedition Program (STEP) for low-income students in Arizona. “It was terrifying at first,” Wong said. “I had never been on a plane before and I had never really been away from my family.” But her time at the Summer Institutes gave her a life-changing glimpse of her future. “There was a sense of community on the campus,” she said. “It was everything I was looking for.” Wong is now a WashU junior majoring in psychology with a minor in Spanish.

In the summer of 2023, Wong welcomed other students to WashU in her position as an assistant for the Pre-College program. “I wanted to give them the same kind of hospitality that I received,” she said.

The programs put the strengths of Arts & Sciences on full display, but Baker emphasized that recruitment isn’t the only goal. “Certainly, many of the students fall in love with WashU and later apply, but our goal is to support the development of college readiness skills that set them up for success no matter where they decide to go to college.”

Buzz at the Brain Bee

Success is clearly on the minds of the dozens of local high schoolers who gather at WashU to participate in the St. Louis Area Brain Bee, an annual competition that tests neuroscience knowledge. Brain Bees take place across the world using materials from the Society for Neuroscience, but the St. Louis competition is a thoroughly WashU affair. Erik Herzog, professor of biology, has been coordinating the local contest for the last 13 years. WashU neuroscience undergraduates write questions for the oral exam, and the winners get the opportunity to spend a summer working in a WashU lab.

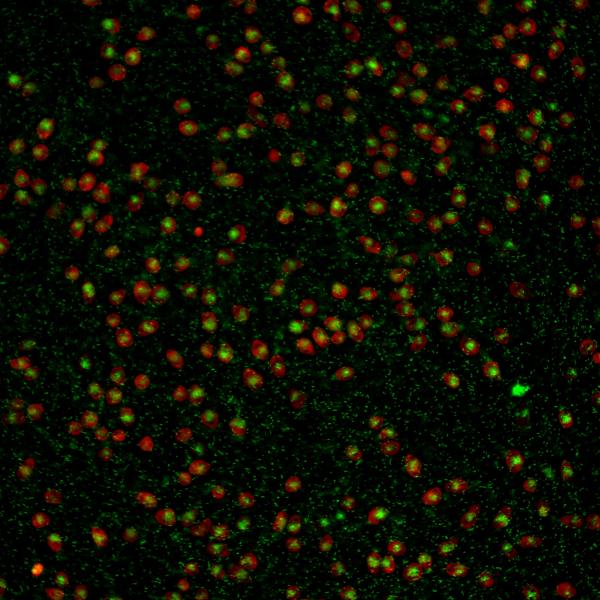

“The Bee is about building connections, both with the material and with other people,” Herzog said. The 2023 competition drew 54 students from 15 local high schools. The winner, Sanjay Adireddi from Ladue Horton Watkins High School, went on to place third at the national bee at the University of California, Irvine. Adireddi spent the summer of 2023 working in Herzog’s lab, where he learned to genotype mice for a circadian rhythm experiment.

The Bee has a long history of attracting students to the field of neuroscience. Shelei Pan, now a WashU senior in the biology neuroscience track, participated in the Bee every year from 2017 through 2020, always finishing in the top five. She said she was initially intimidated by the Bee, but her mother — Xiaoyan Fu, a staff scientist in the School of Medicine’s neuroscience department — encouraged her to give it a try.

“Before the Bee, I had never thought about neuroscience as something that high schoolers could do,” Pan said. After a surprising third-place finish in her first Bee, Pan took the initiative to start a neuroscience club at Ladue. The next year, a squad of classmates accompanied her to the Bee. “The Brain Bee opened up a whole world of neuroscience to me,” she said. She hopes to eventually become a physician who treats patients while also running a research lab. “I want to be able to study the diseases that I’m treating.”

Call of the great outdoors

WashU researchers have been welcoming high school students to Tyson Research Center since 2008. Susan Flowers, now the education, outreach, and DEAI coordinator at Tyson, helped open the doors by securing funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) for Tyson’s two flagship programs: SIFT and TERA.

Originally developed as a five-year project, SIFT and TERA have endured thanks to support from Arts & Sciences and other benefactors. The two programs are now deeply embedded in Tyson’s overall mission. “We want to give high school students a chance to authentically explore field research by doing the real work with the real people,” Flowers said. “Students often start thinking about their future career paths before they reach college, but the field of environmental biology is often hidden from them.”

SIFT serves as a gateway for teens to have their first field research experience. Students get to learn the very basics at the picturesque Shaw Nature Reserve, where they are trained in field safety and how to scientifically explore a variety of Missouri ecosystems. Over five days, they hone their observation skills, learn from career ecologists, and design their own experiments.

They collect and identify bumblebees with insect nets (before releasing them unharmed) for the community science project Bumble Bee Atlas, and they even get to burn piles of bush honeysuckle under close supervision. They also eat — a lot. “Food, fire, and fun, that’s the formula,” Flowers said. The goal, she said, is to make ecological research appealing to kids who grew up in the city or suburbs and never spent much time outdoors.

After the training week, SIFT students can earn money by removing invasive species and collecting data on bees, birds, bats, and other Shaw inhabitants. “We don’t pay students to learn, but we do pay them to work,” Flowers said. The nature reserve is a way station for migrating monarch butterflies, so some students become professional butterfly wranglers, capturing and tagging the insects to help track them on their journey to their winter habitat in Mexico. But not all of the work is so pleasant. “Cutting down bush honeysuckle when it’s 90 degrees out can be pretty taxing,” Bartz, the former Lindbergh student, said.

Graduates of SIFT can later move on to TERA, a more rigorous program in a more demanding environment: the steep, tree-covered hills and ravines of Tyson Research Center. Here, students work alongside Tyson staff and WashU faculty to complete research projects on topics such as forest dynamics, plant diseases, bat species diversity, and the ecology of ticks and mosquitos. Thanks to their previous training, TERA students hit the ground ready to contribute. “They’re full-fledged members of the research teams,” Flowers says.

Bartz’s work with white-tailed deer showed her what it takes to be an ecologist. After identifying individual bucks by their antler patterns, she used geolocated photos to painstakingly track the movements of each animal. “I’m learning about data management and all of the work that goes into the flashy results that scientists achieve,” she said.

Bartz plans to continue working with Tyson as an undergraduate research fellow. She’ll continue her own research while mentoring the next batch of high school students. She’s looking forward to sharing her tips for collecting data, but it might be her enthusiasm that leaves the biggest impact. “I’m a big fan of Tyson,” she said. “It really jumpstarted my career.”