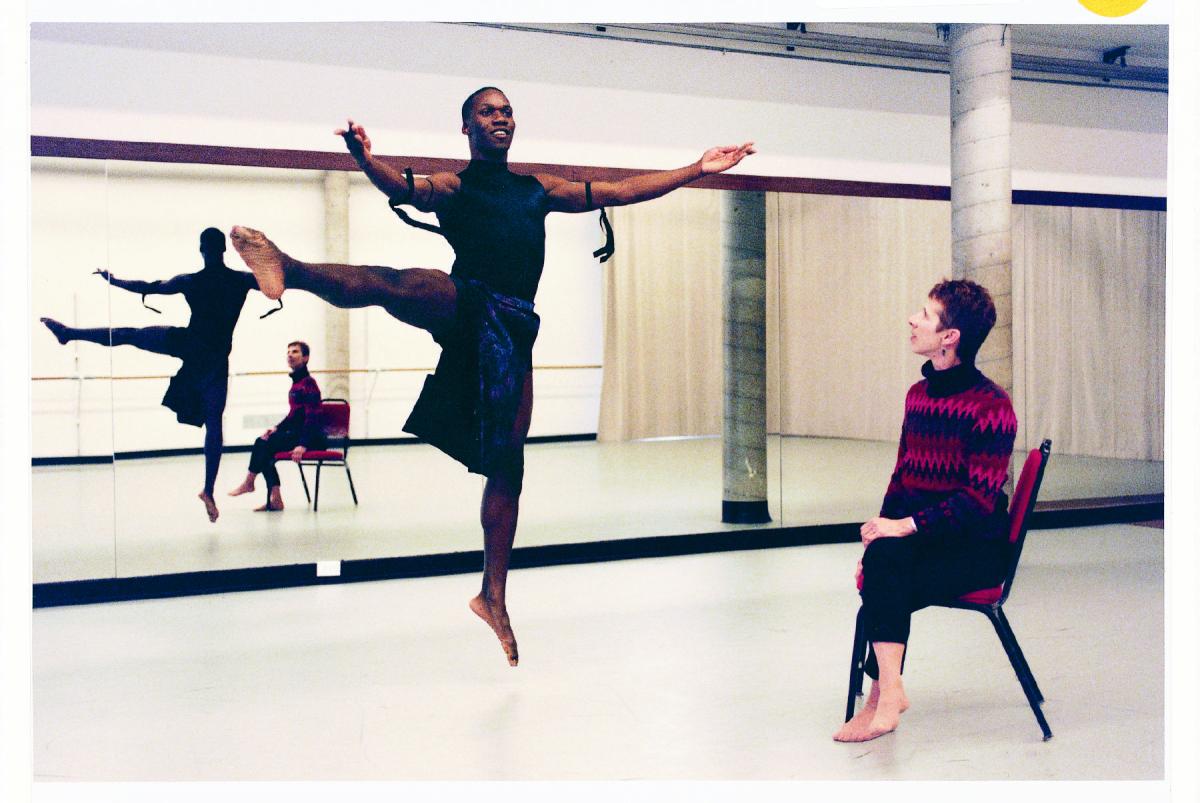

After 42 years, Mary-Jean Cowell is retiring from her position as an associate professor of dance and coordinator of the dance program in the Performing Arts Department. She sat down with the Ampersand to reflect on her time at the University, the importance of dance, and what she plans to do next.

What brought you to the university?

A combination of circumstances, beginning with Annelise Mertz, who founded the dance program at WashU. My family moved to St. Louis, and I studied with her as a high school student in a University College class. My previous training since age five had been ballet, and I knew nothing about the “Modern Dance” that Annelise taught. But Annelise was clearly an artist, and she was able to convey her passion for dance and her conviction of its importance in human experience. She insisted that dance made tangible things not communicated in words or in other art forms. Modern life demanded new, ever-evolving modes of artistic expression, so she emphasized that dance students needed to take an interest in other art forms and consider how the arts related to all aspects of life: politics, sciences, literature and so on.

From childhood, I had loved dancing and school. My high-school self planned to one day teach social studies. However, this new dance experience connected my own passions and gave me the conviction that dance was just as important as other things I could do. I majored in art history and French, while continuing to dance through college. But then dance won. Annelise and I stayed in touch while I pursued a post-graduate career in dance in New York and Japan. (I had also done all of my course work for a Ph.D. in Asian Studies--Japanese Theatre and Literature--while dancing in NY.) She invited me to teach for a semester at Washington University while I was teaching and choreographing for a professional theatre company in Japan.

Three days after I left Tokyo, I walked into the Mallinckrodt dance studio to face my first college dance students in five years. I loved the enthusiasm of the students, their eagerness to try new things, and their desire to have systematic dance training as part of their college education. Instead of returning to NYC, I stayed here, continuing my involvement in performing and choreographing along with teaching. The combination of these pursuits, however, meant that it took me a long time to complete my PhD!

What are some of your most memorable moments as Dance Faculty member?

I’ll have to generalize because there are so many. These memories often revolve around watching students grow out of limiting self-assessments. Like the student who told me on the first day of an introductory course “I’m taking this course because I’m Pre-Med, but I don’t know where my body is.” And he “found” his body and discovered how much could be felt and expressed in movement. Or the student who described herself as “hopelessly awkward although I do really well in...” She typically sat a bit slumped on the edge of the group of students talking before class started. Then she fulfilled a brief choreography assignment with a dance that blew away the class in its inventiveness and clarity of performance. The spontaneous enthusiastic response changed her attitude and movement for the rest of the course. And I’d like to think that she, like many others, learned the gratification of accomplishing something that seems so difficult or at least outside one’s “comfort zone.“

With students at more advanced levels, the memorable moments are often seeing the dancer struggle for weeks to consistently perform demanding movement in his/her own or someone else’s choreography and then totally master it, expressively as well as physically. Just watching one dance major develop from freshman to senior year involves a lot of memorable moments. The senior honors projects always reflect the intersection and digestion of so many aesthetic concepts and personal reflections along with the movement development. And I’m sure that the recent final project (thesis) concert of our first MFA cohort will go into the “best memories” file.

Why do you think a dance program is important at a research university?

A simple yet important answer is that dance studio work offers a different kind of learning experience, one that demands the integration of many human capacities: movement, individual expression, analytic as well as intuitive awareness of time, space, and energy. If a student says that he takes a dance class for relaxation and fitness, I often feel that what he means is: “I want an outlet for capacities and possibilities not fostered in my other courses.” If you play the piano, you get stronger, more flexible hands, but the motivation and benefits go beyond that.

Life is more interesting with an enhanced awareness of movement and its expressive potential—one’s own, others’ movement, the professional dancer’s—and with the sheer pleasure of moving rhythmically and creatively. Everyone has the capacity to “dance” if it is thought of more broadly than a process of mastering a particular vocabulary of steps, some of which may demand years of training to achieve. I have no problem with a dance course being “fun” as long as the student learns the discipline of the art and recognizes that achievement is, as in most fields, relative to one’s consistent focus, rigorous effort, and persistence in the face of difficulties.

The format of a studio dance class creates a supportive community in which students interact more personally and support each others’ efforts to try out new methods and concepts. Moreover, the concrete experience of dance alerts students to its connections with other disciplines that they are studying, such as the natural sciences, psychology, languages, and literature, and to consider how the objectives and methodologies of these fields may differ from or overlap with those of dance. Creativity, research, and systematic analysis come in many forms even within dance studies, and these processes are specifically explored not just in technique and theory classes but in dance seminars, composition, pedagogy classes, and music related studies.

You have degrees in both dance and a PhD in Japanese literature? What made you pursue Japanese literature?

The chair of my master’s program in dance had just returned from a Fulbright in Japan. She announced that I would love classical Japanese theatre “because there’s so much dance in it.” I knew nothing about Japanese culture but began reading about it while I danced in NYC. Actually, when I applied to Columbia, I intended to study Japanese theatre through course work in both Asian Studies and the Theatre School. The year I entered, the budget for Theatre was cut by 40% and some of the courses, some of the faculty I hoped to work with, disappeared. However, I needed to learn the Japanese language and had always enjoyed literature. So ultimately, I ended up reading scripts of Noh and Kabuki, later, contemporary Japanese drama and poetry, supplemented by training in Japanese dance in Hawaii and Japan. This led to the opportunity to teach modern dance and choreograph for the Abe Kobo Studio, a Tokyo repertory company. All of this experience led me to a profound appreciation of the aspect of Japanese culture that sees art as an essential component of human experience—not just an “add-on” if you have the time and money. Many people in Japan pursue practice of the arts consistently for years and achieve high levels of accomplishment with no intention of working professionally. Consequently, the appreciation of the arts and the artist tends to be higher than in the United States.

How did you begin your research on Michio Ito? Are you planning to finish your book now that you'll have time to do so?

Yes, I do plan to add to the five chapters in draft and finish the book. I knew nothing of Michio Ito (“the forgotten pioneer of American modern dance”) until Satoru Shimazaki taught at Washington University for a few years in the 1980’s. He was a leading practitioner of the Ito method but had come to the US to study American modern dance. He was shocked at the lack of awareness of Ito in the US and encouraged me to write a much needed book on Ito because of my experience in Japanese culture and my knowledge of American dance history. I learned a little Ito technique and repertoire from Satoru but was too involved in my own choreography to really focus on it then. In the 1990’s, I began publishing articles and working toward greater competence in the Ito method. Since 2007, I’ve spent a lot of time doing workshops and conference presentations to demonstrate the contemporary as well as historical importance of his method.

If you could go back and give 1976-self advice what would you say?

My 1976-self was so busy enjoying choreographing, performing, teaching, and researching that she probably would not have listened. Or the advice would be what I offer to any WashU student and what I was already doing: do something you love doing and that is of service to others as well as yourself. That will be the most gratifying.

What other plans do you have in retirement?

Dancing in my living room, if nowhere else. More writing after the Ito book. Maybe a little intergenerational teaching of the Ito technique if I find interested participants. Travel to stimulating places, especially those with mountains and/or cultures unfamiliar to me. Gardening both flowers and vegetables. Nothing tastes as good as what one grows oneself.

This is only an excerpt from a longer interview with Mary-Jean Cowell. Visit the Performing Arts Department website for her thoughts on the evolution of dance studies in the university and some of her most cherished memories.