In a letter nominating biology professor Barbara Kunkel for the 2016 David Hadas Teaching Award, a distinction that recognizes excellence and commitment in teaching first-year undergraduate students, the nominator details Kunkel’s energetic and successful efforts to lead and improve Biology 2960. As course master for this large introductory course, Kunkel revised the curriculum, improved the implementation of ‘clickers,’ introduced peer-led discussion groups called “Biology Learning Teams,” and more, the letter says.

Kunkel credits some of her teaching strategies to the NAS-HHMI Summer Institute for Biology Teaching, which she and two colleagues attended in 2013. “I learned just so many fundamental things about teaching that I didn't know. Looking back, they make perfect sense. But I just had not been aware of them,” she recalls. “I wasn't brought up in the culture of grooming myself to be a teacher. I was groomed to be a professor and to do research and run a research group."

"It takes more than just being enthusiastic about a topic to be a good teacher.”

From years of experience, as well as professional development opportunities like the Summer Institute, Kunkel says that one lesson stands out: “I guess what I learned, and it actually took me a while to learn this, is that it takes more than just being enthusiastic about a topic to be a good teacher,” she says. This may be especially true for teaching first-year students in an introductory course like Biology 2960. “There's a very diverse group of students based on preparedness levels, based on interest, based on understanding what it takes to be a good student. They need a lot more. The course has to be put together differently, and the lecture has to be put together differently. Enthusiasm isn't enough.”

One of the fundamental teaching principles that Kunkel has embraced and is trying to incorporate into her courses is “backward design.” With a limited amount of time to teach students important concepts, it’s helpful to identify up-front what students should learn and the skills they need to master. From there, teachers can work backward to design lectures and teaching materials based on those goals. Kunkel also implements active learning – for example, she encourages students to draw diagrams to help them clarify biological processes and concepts, rather than simply read their lecture notes over and over.

Kunkel appreciates seeing first-year students get excited about topics they have never been exposed to before. “To see the diversity of students and what their motivations are for taking this class, and what do they think they want to do when they graduate,” she adds. “That's always really fun. And also helping a student understand something when they were confused, perhaps by explaining it to them a different way or getting some one-on-one time with them. That's really rewarding,” she says. Yet even after receiving the David Hadas Award for excellence in teaching first-years, she still sees challenges for helping new students succeed.

“There are some fundamental issues that I think we need to help our freshmen with,” she explains. “For example, helping them understand what responsibilities they have for their own learning. If something is not clear to them, they should seek out help.” She acknowledges that there are a variety of reasons students don’t seek assistance or input. “Some of them were straight-A students in high school, and they think they've got it figured out,” she says. “So it would be really worth the faculty trying to figure out what's at the bottom of that, so that maybe we can actually come up with different ways to help the students make those connections.”

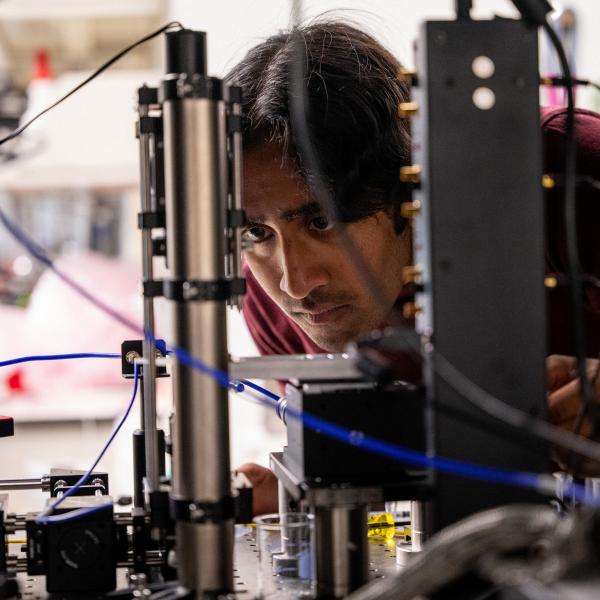

"One of my fantasies would be to have some freshmen get involved in research earlier"

Going forward, she also hopes to give more undergraduates opportunities to work in a laboratory. “One of my fantasies would be to have some freshmen get involved in research earlier, especially those students who may not see themselves as biologists or see themselves as scientists,” she says. “If there was a way to get them involved in research – in my lab or somebody else's lab - earlier on, so that they could actually say ‘I can be a scientist, or I can be a biologist,' they might engage and feel more confident in the material.”