The rovers Spirit and Opportunity are dead. Now what happens to the terabytes of data they collected?

In June 2018, the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity succumbed to a massive dust storm, the largest researchers have ever seen on Mars. NASA officially declared “mission complete” in February 2019 after numerous failed attempts to hail Opportunity, which had already outlived its twin, Spirit, by nearly eight years.

The death of Opportunity revealed how deeply and emotionally viewers on Earth had connected with the mission. The rovers offered a uniquely human perspective on the Martian surface, vastly different and much more intimate than the orbiter’s-eye view we had before. Though the mission’s deputy PI, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor Raymond E. Arvidson—known by others on the project as the “Stoic Swede”—said he did not shed any tears over the death of Opportunity, he understood how researchers and members of the public who had spent years following the rover could feel deep affinity with the machine.

“It’s just metal and bolts and stuff. It’s not a person,” said Arvidson. “But this is a vehicle that’s acquiring data with the acuity of the human eye at the height of a person in a terrain that looks eerily like the Earth. It’s a much more human experience, so people got attached to the rovers, like you might get attached to long-lost cousins.”

“It is special, but the rover couldn’t go on forever,” said Arvidson. “Now we have all the archives that will live for decades.”

The Mars Exploration Rover mission began in the early 2000s. Two rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, were launched in 2003 and landed on Mars in January 2004. The mission was simple: Follow the water. “By looking at the ancient rock record, we could investigate the extent to which Mars was warm and wet in early geologic time,” Arvidson said. Both rovers landed successfully and began what was designed to be a mission lasting only three to six months and covering just a few hundred meters of Martian terrain. By all metrics, both rovers far exceeded expectations.

“We followed the water, and we found dramatically amazing evidence for water being in the ground and on the surface billions of years ago. We found places that would have been habitable.”

Spirit landed in Gusev Crater, an area roughly 4 billion years old that was believed to be an ancient lake bed. But instead of the formation researchers were expecting to find, the crater turned out to be covered in basalt from an old lava flow. Undaunted and fortunately placed, Spirit traveled to nearby Columbia Hills, an ancient chunk of Martian crust that was not fully covered by the lava flows. There, Spirit found evidence for past water, largely in the form of groundwater that had corroded the rocks.

Spirit took one more trip to Home Plate, an eroded volcano named for its resemblance to a baseball diamond, where Spirit found evidence of fumaroles, hydrothermal vents, and silica deposits, similar to what’s present at Yellowstone. “The silica is important because we’ve discovered that high-silica deposits on Earth are great for trapping microbes,” Arvidson said. “The key thing that Spirit found is evidence for warm, wet conditions with a lot of water interacting with this emerging volcano.” In 2009, after five years on Mars, Spirit was way out of warranty and starting to have problems. NASA officially ended its mission in 2011.

Opportunity’s story is even more remarkable. The rover landed on Mars’ Meridiani Planum, chosen because from orbit it appeared to contain crystalline hematite, which forms in the presence of water. What Opportunity actually found was hematite concretions, or little balls of hematite. These concretions—called “blueberries” because they’re not as red as the rest of Mars—are found all over Earth, but on Mars their implications are stunning.

“We totally lucked out,” Arvidson said. “Opportunity bounced into Eagle Crater, and only five meters away on the wall of the crater were these rocks that—in terms of their chemistry, mineralogy, and structures—said, ‘I formed in an ancient lake.’ The formation would have demanded extended periods of liquid water on the surface. So, even if we never left the crater, the mission would have been a success. We were ecstatic. Little did we know that we would drive over 45,000 meters and last 14 and a half years.”

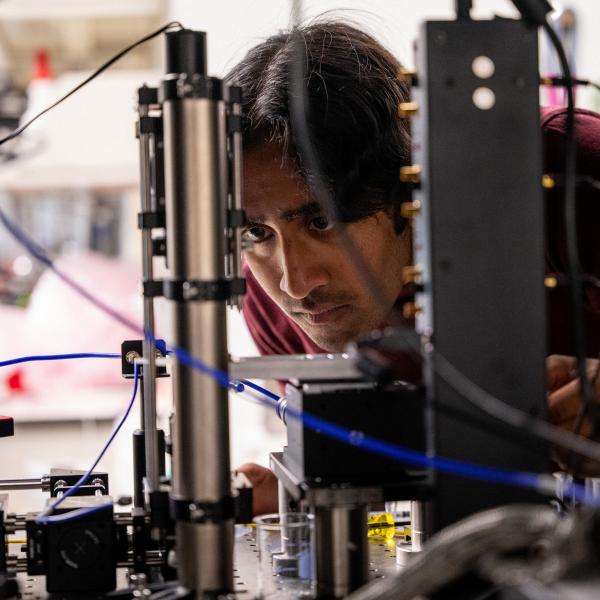

Though it might not have the same power to tug heartstrings as the rovers themselves, the data that Spirit and Opportunity collected is unprecedented and invaluable for future research. The Geosciences Node of NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS), one of six discipline-specific nodes located at institutions around the country, is housed in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at WashU, under the care of Arvidson and a team of archivists. It is the lead archive for all landed missions to Mars, preserving data that will be mined by researchers for decades to come. The archive includes details about both rovers’ every move as well as many images that helped this mission capture the public’s imagination.

Once the mission ended, archiving efforts took center stage, leading up to the true end of the project in September 2019, when all servers were closed down and all archiving was declared complete.

Susan Slavney, a programmer and analyst on Arvidson’s team, has worked on the archives for 35 years—after taking what she thought would be a summer job in 1983—and contributed to the mission’s overarching data collection and storage strategy. “From the beginning, part of the mission’s criteria for success was to create a publicly accessible archive,” Slavney said. “We started working with each instrument team years before they got to Mars to develop a plan for what their archives were going to look like, how they would be formatted, and how everything would be documented.”

Slavney was part of the data and archiving working group that was responsible for setting archival standards for the Mars mission and releasing data to the public on a regular schedule, following the rovers’ successful landings. Arvidson noted, “She’s the boss on the PDS side of the working group. When Susie speaks, PDS people listen.”

The success of this archive has since set the international standard for data collection, curation, and distribution. “The idea is for planetary data agencies to work together to develop and adopt common standards, so we can share data and tools with the planetary community worldwide,” said Thomas Stein, computer systems manager with Arvidson’s group and former chair of the International Planetary Data Alliance (IPDA). The practices established by Slavney, Stein, and the rest of the PDS archiving team have been implemented by agencies around the world, including the European Space Agency (ESA), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO).

Arvidson and Slavney fondly recalled the humble beginnings of the Geosciences Node, which was previously housed in the basement of Wilson Hall on WashU’s Danforth Campus. Not surprisingly, Slavney said the biggest change in the data archiving game in the last 35 years has been the World Wide Web. “It’s much easier to move information now. Even huge amounts of it. Before the web, we were mailing things out on CDs!”

Now, anyone aiming to experience a day in the life of a rover can access the mission’s data and contextual details in the Analyst’s Notebook, which is available through the PDS website. And in this regard, both Spirit and Opportunity will live on indefinitely.