Recent missions by NASA, SpaceX, and other international outfits have put space exploration back in the public eye. In this Q&A, Bradley Jolliff, new director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, describes current collaborative work in the space sciences at WashU and looks forward to the next generation of research.

Bradley Jolliff, Scott Rudolph Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences, took over as director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences (MCSS) in fall 2019, becoming the center’s fourth director since its inception in 1975. Here, Jolliff, who has been affiliated with the McDonnell Center since he started at Washington University as a postdoctoral fellow in 1987, discusses his approach to leading the internationally known center in a time when space has once again captured the public imagination.

What distinguishes MCSS as a key collaborative center at WashU?

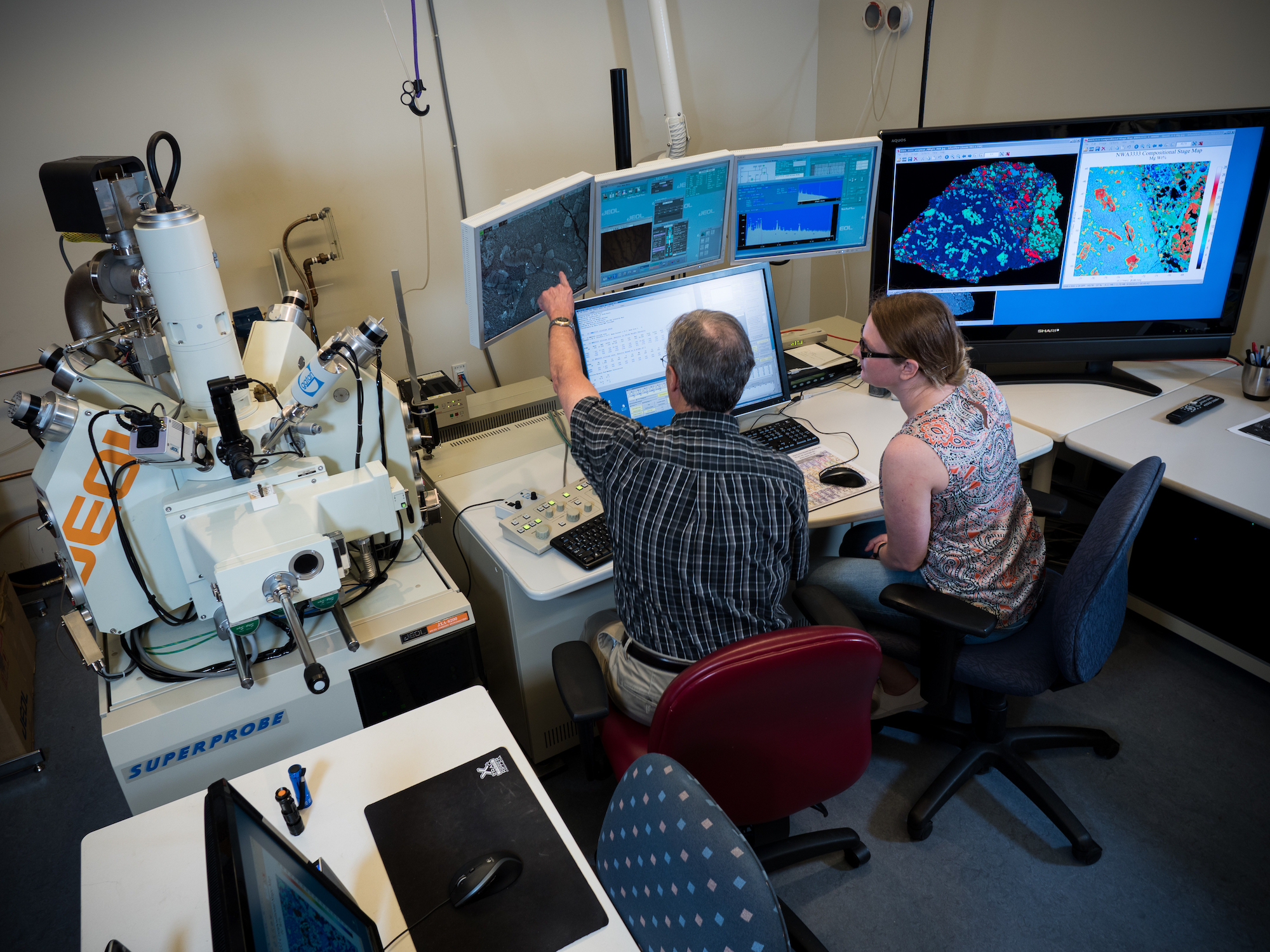

Since it was founded in the mid-1970s, and even more so into the ‘80s, the McDonnell Center has been known as a place where researchers go to work on extraterrestrial samples, be they Apollo samples or meteorites or star dust. The center has developed an international reputation as a major collaborative endeavor, centered on our world-class laboratories here on campus. We have a cluster of cutting-edge facilities housed in Compton Hall and Rudolph Hall. During the tenure of inaugural director Robert Walker, all the labs on the fourth floor of Compton were open – no locked doors. Even now that we’ve expanded, the facilities are still close together, fostering collaboration and interactive research.

Over the years, MCSS has done a lot to develop campus research facilities. Are any new facilities in the works?

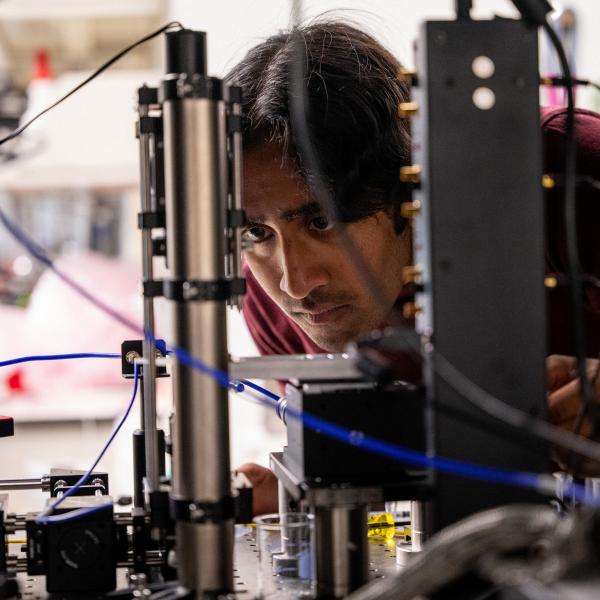

One of the hallmarks of the McDonnell Center is establishing really fantastic laboratories. Again, that dates back to Bob Walker’s vision of working on lunar samples in the ‘70s and his efforts to develop next-gen instrumentation like the NanoSIMS, which is still used to find isotopic anomalies in astromaterial samples today.

I’d love to have the vision to say, “Oh, I know what the next big instrument and area will be!” But I don’t have to do that because we’ve got a number of brilliant scientists associated with the McDonnell Center who are already pushing those boundaries. To give a few examples, just this past winter we had the SuperTIGER balloon mission in Antarctica studying the origins of cosmic rays. The XL-Calibur telescope recently received funding to follow on the success of X-Calibur. Another team, led by research professor Jeff Gillis-Davis, is investigating water and space weathering on the Moon in part by developing a laser laboratory for simulating the harsh space environment. Folks in the McDonnell Center are doing the work to develop new instruments and facilities. The center supports them through endowments, and by doing so we know we’ll be making measurements at the frontier of understanding the cosmos.

What are your top priorities for the future of MCSS?

I want to see us doing next-generation research in astromaterials and in astrophysical phenomena. That’s a big research priority for me. But in reality, what I do as the center’s director has more to do with personnel. I’m focused on supporting our people, our brilliant scientists, including a lot of young scientists. I want to make sure that we have a good program for bringing young people, undergraduates, and graduate students into the labs because that’s how we grow.

The best research facilities not only have cutting-edge instrumentation, they also have amazing research groups who can work synergistically. This is an area that’s been negatively impacted by COVID-19 because we really work better when we’re in the lab together and interacting and asking questions of each other. Younger researchers especially ask the best questions. Oftentimes that leads us to think beyond the box a bit.

What’s your favorite thing about being director of MCSS?

Getting to know all the people who are doing different things in our affiliated departments and beyond. Our core people are in earth and planetary sciences and physics, and we have affiliates in the engineering school and in the biology and chemistry departments. So it’s really fun to learn about the range of activities our students, postdocs, faculty, and other researchers are undertaking.

With the recent launch by NASA/SpaceX, the general public is showing a renewed interest in space. What are some ways MCSS supports this interest, both locally and more broadly?

We think a lot about how we interact with the public. It’s easy to get focused on research and get too technical. We strive to communicate our work in ways that make it understandable. Luckily, we have wonderful resources. One of our greatest resources is the young membership of the center. We get a lot of calls to work with local schools and other regional groups. Our younger members are really good at visiting with educational organizations and interacting with the public, communicating the excitement of what we’re doing, and sharing the space sciences with the next generation of aspiring scientists.

What one thing would you want people learning about MCSS for the first time to know?

I’d want people to understand the history of the McDonnell Center and how it continues to guide our mission today. When MCSS was founded, scientists were thinking about new samples from outer space, new samples from the Moon, and what they can tell us about the processes going on in the solar system and the universe beyond. It’s the vision and the excitement associated with those early discoveries and questions that form the core of the McDonnell Center.

That same spirit leads us to the great breadth of research that’s being done today. We’re involved in the Mars rover missions, looking for habitable environments on Mars and possibly the origins of life elsewhere in the solar system. We’re seeing the images from the New Horizons flyby of Pluto and now the Kuiper Belt object, Arrokoth. We’re analyzing old Apollo samples with new instruments and supporting the next generation of researchers. When MCSS first started, we were in discovery mode, and we still are today. It’s a wide-open frontier.