Elizabeth Korver-Glenn discusses her 2021 book that looks at the ways racial segregation impacts the U.S. housing market.

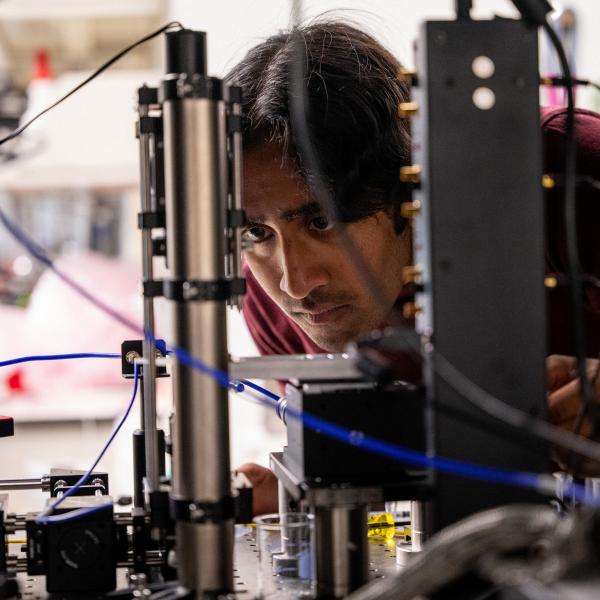

Elizabeth Korver-Glenn, assistant professor of sociology, studies how cities and housing markets reproduce inequality, and how public policy can maintain or mitigate it.

In 2018, when Korver-Glenn was at the University of New Mexico, she and her collaborator Junia Howell published a paper showing that homes in Black and Latino neighborhoods in Houston were valued at less than twice the amount of homes in white neighborhoods, even after accounting for several factors like property size, school district, and crime.

They expanded their research to roughly 100 of the largest metro areas and found a similar outcome. Their research revealed that neighborhood racial inequality in housing values persisted despite policy changes resulting from the 1968 Fair Housing Act. In fact, between 1980 and 2015, inequity actually increased.

Their study, published in 2020, garnered immediate attention. Korver-Glenn was featured on ABC's “America Lowballed,” a documentary that followed several Black families who 'whitewashed' their homes — taking down family photos, having white friends present at the property — in order to receive equitable appraisals. Organizations including the Appraisal Institute and The Appraisal Foundation invited Korver-Glenn and Howell to present their findings to members. The Biden administration also took notice and created the Property Appraisal and Valuation Equity Interagency Task Force, which published an action plan citing their research.

Since then, Korver-Glenn has been working on several new projects. Her book “Race Brokers: Housing Markets and Segregation in 21st Century America” came out in 2021, the year before Korver-Glenn joined the sociology department at WashU. She sat down with the Ampersand to talk about her book and the impact of racial segregation on the housing market.

Your book “Race Brokers” argues that racial segregation in housing is one of the key mechanisms at the core of inequality in the United States. Can you explain what you mean by that?

In the United States, we have decided that where someone lives determines where they go to school. It determines how close they are to employment opportunities, health care, and even transportation options. And a century ago, when the Roosevelt administration was trying to dig the country out of the Great Depression, it institutionalized many housing market practices that have persisted to this day. This includes not only what we colloquially understand as “redlining,” but also things like determining a home's value or listing a home for sale in ways that explicitly treat homes in Black neighborhoods and other communities of color as worse than homes in white communities.

As a result of the widespread institutionalization of these federal and local policies and programs, our housing is inherently racially unequal, and that inequality cascades down to other arenas.

You also talk about how individual actors and common practices in the real estate industry add up to a racist system. What are some of the decisions or entry points you’ve identified that contribute to this structure?

I talk about four main sets of actors in the real estate profession: housing developers, real estate agents, mortgage bankers, and appraisers. They aren’t making up the practices as they go, they are acting in accordance with the industries and organizations in which they are embedded.

Our research demonstrates that, in many ways, it doesn’t matter whether an individual appraiser or agent is racist because as long as they still use long-held logic and methods — like those required by the federally backed mortgage lenders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — they infuse racial inequality into the process.

One example is the percentage-based commission for real estate agents, which means that agent pay is contingent upon home value. Because agents routinely draw on racial stereotypes of white homes being of higher value than Black homes, agents work harder to recruit white clients and work harder to sell their houses once they do. It’s a self-reinforcing system.

When you were researching your book, you said that one real estate professional after another told you that segregation is “natural,” and that people “just want to be around others who are like them.” What’s your reaction to the belief that segregation is inevitable?

The reality is that real estate professionals shape housing options and the choices American consumers make. For example, real estate agents actively steer buyers to certain neighborhoods based on race.

I think it’s important for people to know that the Fair Housing Act of 1968 did not necessarily bring great progress. We’ve made some gains, but we have very little empirical evidence that it's been effective in promoting racial equity. In these everyday interactions between real estate professionals or real estate brokerages and consumers, the market still hinges on racism in a way that I don't think the public has been willing to admit. We have to be aware of the processes that are happening not only behind the scenes, but out in the open.

What are some interventions that could help the real estate industry strip away some of the hidden practices that reinforce racial segregation and inequality?

In the book, I give three major categories of interventions. The first is monitoring real estate professionals and industries. At the moment, for instance, there are no boards or databases of licenses for housing developers. We should have some kind of basic training for the people who decide where to build homes — or at least we should know who they are.

Second, there are legal approaches. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 has many benefits, but it does not address some of the fundamental issues I uncovered in my research. But things like the sales comparison approach — when home values are determined based on the price of homes in the same neighborhood only — could fall under the notion of “disparate impact discrimination,” which is illegal under the Act.

Finally, there are direct interventions, like getting rid of the market area maps published by real estate boards, which implicitly signal neighborhoods of color. Another direct intervention would include going undercover, calling out and exposing things like reverse blockbusting.