Last spring's undergraduate field geology trip was nearly derailed by the coronavirus pandemic. Though the destination changed mere days before the group’s scheduled departure, the trip was ultimately a success.

Like so many events last spring, the annual undergraduate field geology trip was nearly upended by the coronavirus pandemic. Originally planned as a trek across the Andes, the trip was moved to Sicily, in southern Italy, in late October to avoid the rapidly deteriorating political situation in Chile. Then, in late February, as the coronavirus spread around the world, the trip had to be moved again to the southwestern United States only days before the group’s scheduled departure. The same travel restrictions that made Italy unreachable also cut short the Utah expedition by several days. Despite these challenges, the field trip was a success, thanks in large part to nimble organizers and adaptable students.

“We knew that COVID was coming, but we didn’t know how quickly, and we didn’t know where,” said Phil Skemer, associate professor and co-instructor of the undergraduate field geology course. “I was in Paris in late January, and already everyone was pretty nervous about traveling, but it hadn’t really appeared in Europe yet.”

Fast forward to February 21, a mere two weeks before the planned trip to Sicily. Cases had started to appear in Lombardy in northern Italy, and Skemer was worried. He and co-instructor Alex Bradley, associate professor, were keeping a close eye on the Johns Hopkins coronavirus tracker. They hoped that Sicily, hundreds of kilometers from the outbreak in the north and (at that time) apparently untouched by COVID-19, might still be an option.

These hopes were quickly dashed. By Monday, February 24, Skemer and Bradley knew their plans would have to change.

“We were slightly out in front of WashU at this point. They hadn’t announced any travel restrictions yet,” Skemer noted. “But, we knew that it was only a matter of days before they were going to start limiting people’s travel, especially internationally. So we had to cancel Sicily, and we thought, ‘We’ve got 10 days to come up with a backup. What can we do in 10 days?’”

Answer: Utah.

Though the students had already done much research in preparation for the complicated geology of southern Italy, Skemer and Bradley knew they could offer a robust field experience in the Southwest, making use of the students’ fundamental skills. As a matter of practicality, they also knew they could secure flights, hotel rooms, and rental vans on short notice.

“We’ve always had an idea that the Southwest is the only place we would be able to easily get tickets at the last minute,” Skemer said. Southern Utah – with its abundant national parks and monuments, including Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Grand Staircase-Escalante – was selected, and travel arrangements were quickly made.

Eight days before their planned departure, students had to make a tough call: Stay or go? All eight students chose to go.

“I never considered opting out,” said senior Ellie Moreland. “Sure, I was disappointed we wouldn’t be able to go with our original plan, but from taking the trip last year, I knew it would be enjoyable because of the group of people I would get to go with. I was intent on going wherever we ended up and having a rewarding time with the class.”

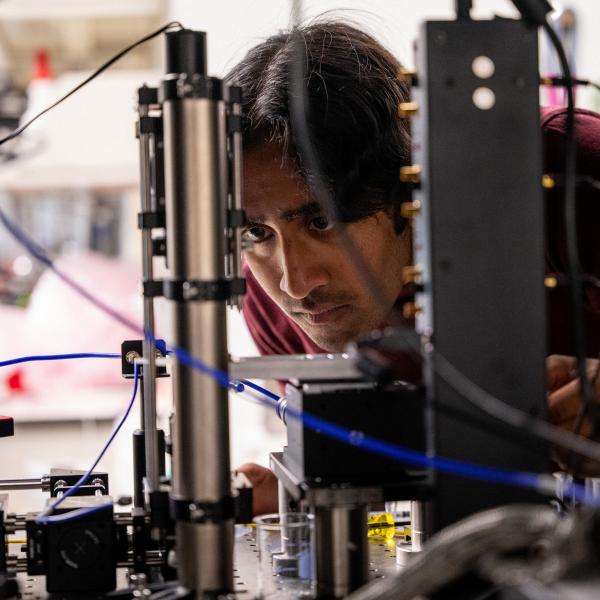

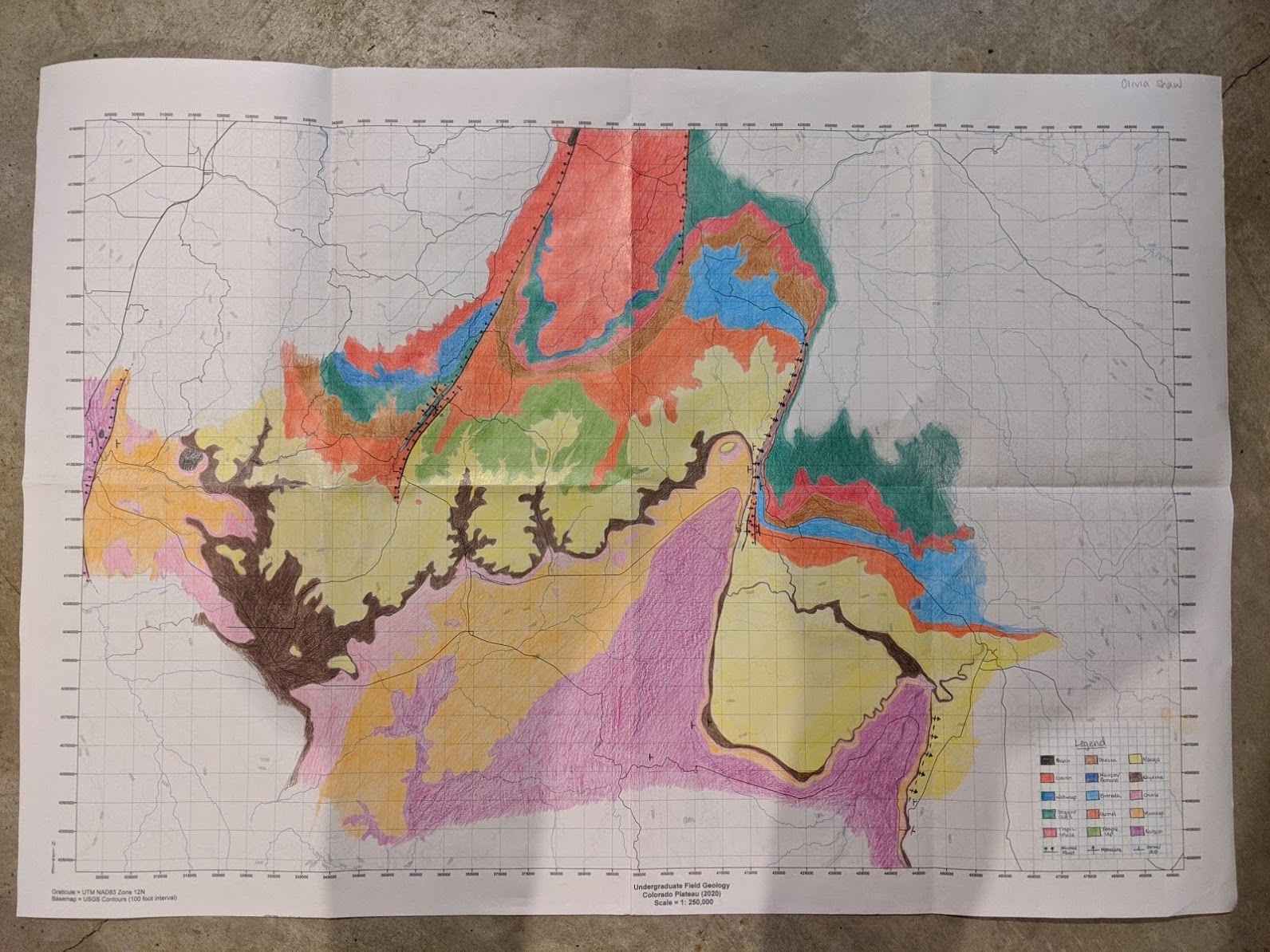

Though the quick pivot from Sicily to Utah meant that some specific activities couldn’t proceed as planned, Skemer pointed out that there are certain skills expected of all students that can be applied in almost any geologic setting – from Italy to Patagonia to the American West. For this trip, Bradley and Skemer turned to Bill Winston, a geographic information systems analyst with Washington University Libraries. With Winston’s help, they created blank topographic maps on large format paper, which the students used to produce geologic maps covering roughly 20,000 square kilometers and four national parks and monuments in less than five days.

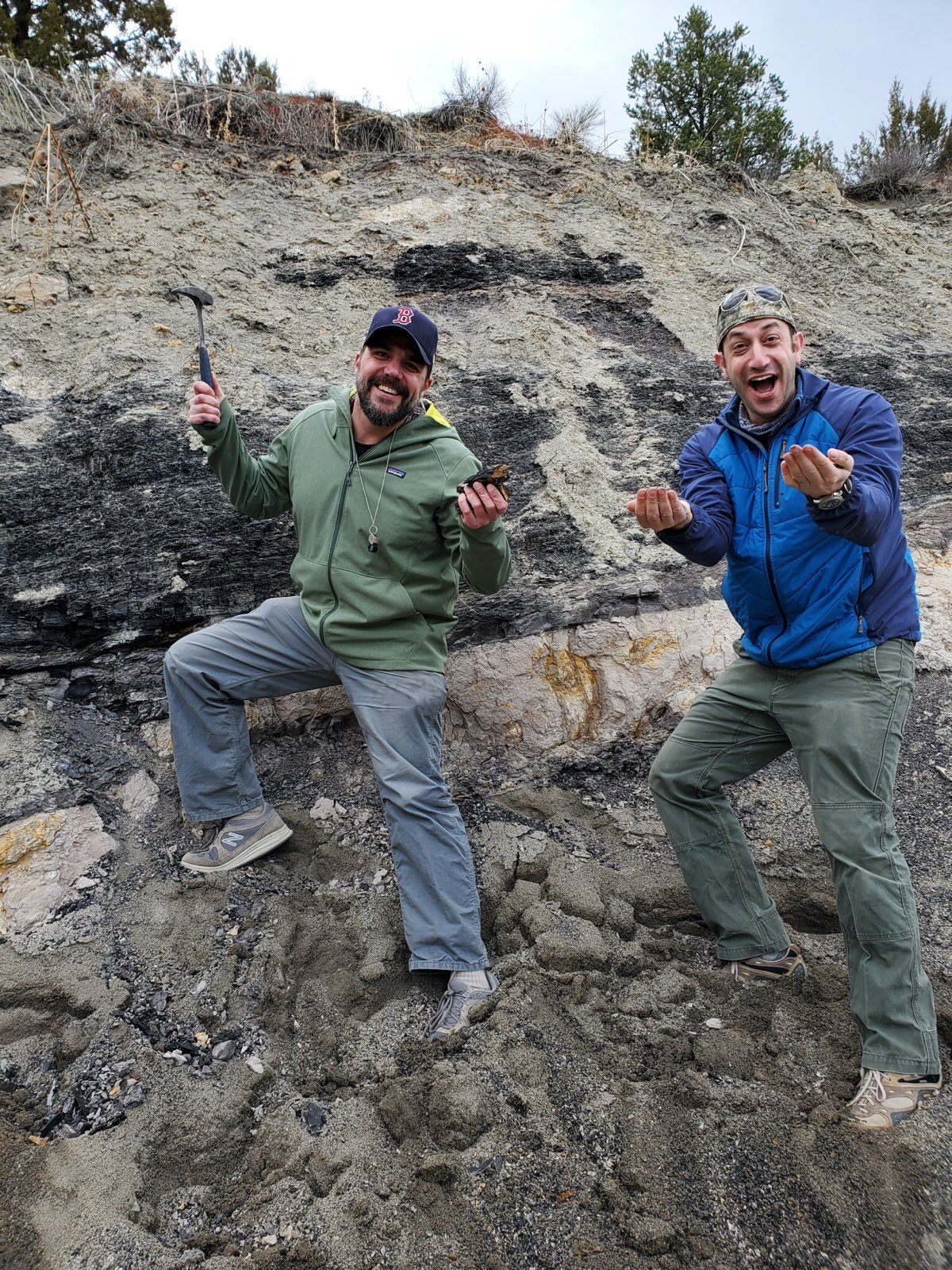

“In terms of geology, southern Utah is spectacular,” said Skemer. “We could see all sorts of things and also cover a huge area. The geologic exposure is fantastic because there’s almost no vegetation. So you can see everything laid out in front of you. Every day we were just driving to different sections of the map with the students in the back of the van making their geologic maps as we went. We’d stop when we saw something particularly interesting and look at the rocks up close. I think they got a lot out of it.”

Moreland agreed: “The trip was absolutely worthwhile – from the geology and field experience to the bonds formed with classmates.” She added, “I think we all did well dealing with the circumstances before and during the trip, and ultimately we made the trip the best it could be. I wish we could have stayed the full week, but the time we had there was well worth it and absolutely positive.”

The group arrived in Kanab, Utah, on Friday, March 6. On Wednesday, March 11, WashU announced that the rest of the semester would be remote. With the university bracing for the arrival of the coronavirus, students and organizers once again had to scramble to modify travel plans. They flew back to St. Louis on Thursday, March 12, so students could pack their things and return home by Friday, March 13.

Since Skemer and Bradley started offering the undergraduate field geology course eight years ago, the class has been an important capstone for students, taking their education beyond the classroom and into the field. Traveling with a group isn’t easy – even without a major global crisis – but ongoing support from the university and the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences makes this critically important educational experience possible.