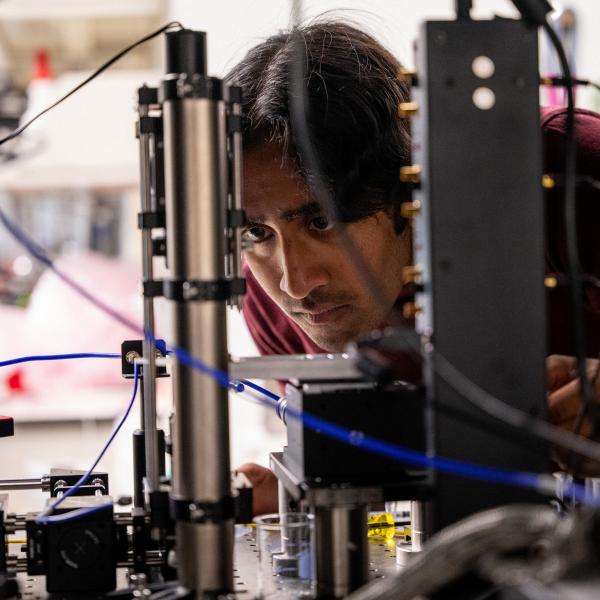

Brent Rappaport, a clinical doctoral student working with Deanna Barch in the Cognitive Control & Psychopathology Lab, seeks to understand the effects of bullying on adolescent brains and behavior.

The TV show “Survivor,” now in its 39th season, has spawned hosts of spin-offs and adaptations. Most cater to reality-TV lovers worldwide, but one surprising variation has become part of the toolbox researchers use to understand the effects of bullying on adolescents.

Bullying is known to be a risk factor for depression, especially among young people, but scientists still know little about how that link really works. Does being bullied cause changes in the brain? Do experiences of peer victimization (the technical term for bullying) change kids’ social behavior, which in turn might lead to depression? Neither? Both? Brent Rappaport, a fourth-year graduate student in the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, recently carried out a study examining these issues.

According to Rappaport, questions about the brain and about behavior often fall into separate research camps. “Right now, it feels like those fields have operated somewhat independently of one another. The neuroimagers do their thing, and the behaviorists do their thing,” Rappaport explained. “There have been theories that bullying can lead to changes in the brain, and theories that bullying leads to changes in the way people behave and interact with their peers. I like the idea of bringing those together and trying to say – maybe it's both.”

In order to bridge this divide, Rappaport collaborated with researchers at Washington University and around the country. He worked with his advisor, Deanna Barch, the Gregory B. Couch Professor of Psychiatry, and Joan Luby, director of the Early Emotional Development Program, along with other researchers at WashU. Autumn Kujawa at Vanderbilt University, who originally developed the Survivor-esque computer task, worked with Rappaport to modify adapt the program for his needs. Kodi Arfer, a research scientist out of UCLA, provided additional assistance with coding and troubleshooting and organizing data. Emily Kappenman, an EEG expert from San Diego State University, provided assistance and insight in the interpretation of the findings. With this national cohort of support, Rappaport was able to move forward with the project.

The study participants, a group of 56 adolescents around 18 years old, were recruited from a long-term project led by Barch and Luby that tracks a number of data points, including experiences of bullying over time. In Rappaport’s study, participants were asked to play a computer game with other adolescents around the country. After each round, the teens voted on whether to keep other players in the game or kick them out. The game simulates the kinds of acceptance and rejection that regularly happens in social situations, but in this scenario, every teenager wore an array of electrodes – allowing the researchers to see players’ behaviors and brain signals over the course of the game. “You can look at the EEG signal when they see a specific stimulus,” said Rappaport, “and in our case, being accepted or being rejected was the stimulus.”

The moments of rejection within the game may seem most worth examining, but instead, Rappaport focused on participants’ responses to being accepted. “A lot of depression research shows reduced brain activity in response to different kinds of rewards,” Rappaport said. In this study, he wanted to test whether a history of being bullied results in a similar effect. After examining the data, Rappaport found that the brains of kids who had experienced bullying did show reduced reactions to social acceptance. “They were less excited at the prospect of being accepted by a peer,” he said.

That insight alone may have an effect on how clinicians help adolescents work through experiences of bullying, but Rappaport was even more excited by the study’s behavioral finding. “The kids that were bullied were more likely to reject other players.” Rappaport stated. “I thought that everyone would just play the game pro-socially, because what's the cost to you to just keep everyone in the game? But no, there's a lot of variation in how willing to accept other people some players were. Some people didn't want to accept anyone.”

From a clinical standpoint, Rappaport sees these findings as potentially helpful for those who have experienced peer victimization. Simply bringing awareness of an increased tendency to reject may be a valuable intervention. As Rappaport put it, “It might be as simple as saying, hey, because you've had this experience, you might tend to try to reject other people. What can we do to curb that tendency?” As teens across the country grapple with the effects of bullying, these types of insights may prove an important piece of knowledge for victims and those who support them.

Rappaport is particularly excited to pursue this work at Washington University, which in his experience has offered “phenomenal” training, especially in statistics. “I feel like I'm always able to do research in the best, most robust way possible,” he said. “The department has been wonderful. I came in with all of these ideas and wanting to study bullying, and even though nobody in the lab had really studied that before, I was encouraged,” said Rappaport. “It feels like we're rewarded for bringing new ideas to the table.”

Rappaport plans to continue his work on bullying, something he says he feels passionate about. While working on a project to replicate the results of the previous study with another group of participants, he is also developing his dissertation on the effects of bullying.

For the full text of this study, see:

Rappaport, B. I., Hennefield, L., Kujawa, A., Arfer, K. B., Kelly, D., Kappenman, E. S., Luby, J. L., & Barch, D. M. (2019). Peer Victimization and Dysfunctional Reward Processing: ERP and Behavioral Responses to Social and Monetary Rewards. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 13, 120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00120